|

|

![]()

| CAMPBELL IAN JAMES SIGNALMAN NX 72540 |

| Singapore - "A" Force Burma - Thailand |

In mid-July 1941 we arrived in Singapore to a welcome of torrents of rain from the blackest of clouds. We were taken by truck from the “Johan van Oldenbarnevelt” across the Causeway to join the first contingent of 8 Division. Signals, who had arrived in May, on “Queen Mary”. We lived in tents, four to a tent, not far from the Sultan’s palace. We found our cooks had brought their Australian July menus with them, featuring porridge for breakfast and two meals of stew.

In mid-July 1941 we arrived in Singapore to a welcome of torrents of rain from the blackest of clouds. We were taken by truck from the “Johan van Oldenbarnevelt” across the Causeway to join the first contingent of 8 Division. Signals, who had arrived in May, on “Queen Mary”. We lived in tents, four to a tent, not far from the Sultan’s palace. We found our cooks had brought their Australian July menus with them, featuring porridge for breakfast and two meals of stew.

We were not given leave until we proved we were fit by running about a mile in six minutes, a course set between the camp and a milestone down the road. As I had run three laps of the Rosebery race-course, where we were in camp, each morning, and had won a skipping competition on the ship, I was fit enough to do this. Unfortunately the main part of my job was to bring the company records up to date, and I recall having about six lots of leave, going to the Singapore Swimming Club on a few occasions. As our signal units were already with the Battalions, radio parts and equipment had to be kept up to them, which meant driving between Singapore and towns on the mainland. Our Company headquarters consisted of a

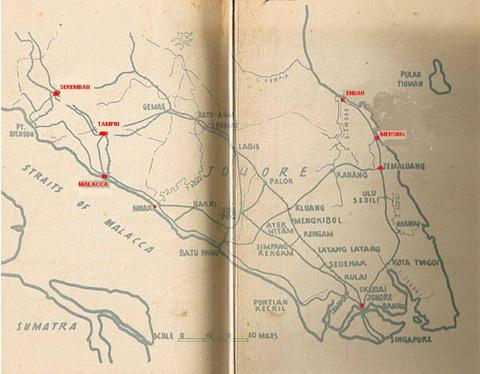

Captain, C.Q.M.S. batman and me. We were the link between our company and H.Q., and the batman and I were to share the driving of our utility. He did most of the driving before the invasion, but became indisposed, and I had to do all the driving. As things worsened it became a case of being on duty twenty four hours a day. We would be in Singapore at 8am to load equipment, then drive to Tampin, then back to Seremban and Malacca, arriving at Johore Bahru well after midnight. Next day would be a visit to our units on the East Coast, at Endau or Mersing and Jemaluang, then back to base in the early hours. Keeping the records up to date in the daytime, and driving most nights through the blackout became a little nerve wracking, but as the Japanese advanced the trips became shorter. I drove through the Jungle by watching the lighter colour of the sky, like a ribbon, between the dark jungle on each side of the road. My worst experience came on the morning we were ordered to cross the Causeway on to the Island of Singapore.

Captain, C.Q.M.S. batman and me. We were the link between our company and H.Q., and the batman and I were to share the driving of our utility. He did most of the driving before the invasion, but became indisposed, and I had to do all the driving. As things worsened it became a case of being on duty twenty four hours a day. We would be in Singapore at 8am to load equipment, then drive to Tampin, then back to Seremban and Malacca, arriving at Johore Bahru well after midnight. Next day would be a visit to our units on the East Coast, at Endau or Mersing and Jemaluang, then back to base in the early hours. Keeping the records up to date in the daytime, and driving most nights through the blackout became a little nerve wracking, but as the Japanese advanced the trips became shorter. I drove through the Jungle by watching the lighter colour of the sky, like a ribbon, between the dark jungle on each side of the road. My worst experience came on the morning we were ordered to cross the Causeway on to the Island of Singapore.

We were at the rear of the convoy comprising British, Indian, and Australian troops moving slowly on the road that led to the Causeway. Spotter planes directed bombers to the group of vehicles, and the result was horrendous. Whole vehicles and their occupants had been blown to nothing; there were dead bodies and bodies torn in half, lying on the road, and all we could do was to get help from the nearest Military Police post, and Casualty Clearing Station (CCS). It was frustrating not being able to help, and shook us up considerably.

We were directed to an orchard near Bukit Timah, where our C.O. ordered a full inspection. Once again this was spotted, and we were subjected to a long artillery shelling. From here we moved back to the Singapore Gardens, keeping in touch with our detachments, and carrying equipment to them. At a British Ordnance store, our C.Q.M.S. requested automatic weapons for our Signalmen and Linesmen attached to the various battalions, and was refused rather rudely. It was extremely galling when some of our men were sent by the Japanese to this depot, where their job was to open many great cases, and pass on to the enemy hundreds of automatic weapons, never used. On another occasion, we had telephones to a unit on the West Coast. We came to some Sherwood Foresters, who told us the Nips were just over the hill. We pushed on and met a Machine Gun (MG) platoon, who told us the same thing. We reached the village, to find our people had moved with the battalion, but a company of Indian infantrymen were there. The officer asked me what he should do. I suggested he go down the coast road to find his unit near Singapore, and we retraced our route. The M.G. were gone and the Foresters had gone too. I drove towards the North hoping to find our Unit, but around a corner about three hundred yards ahead came a Jap tank. I don’t know how, but I was around the other way in two movements and heading the other way, expecting a shell to come through the back of the ute, but it didn’t, and we arrived back at the Gardens in one piece. Next night I drove two specialists to a junction box near Bukit Timah, to destroy the wires leading to the city. The town was alight, and shells from both sides were whistling overhead, those falling short causing the blaze. While waiting, I walked to a mile post, and found an officers map case on top of the post, marking all our positions. I took it back to H.Q. as soon as we got out of the burning town.

I drove two officers to a house in Hollands Road, where Generals Wavell, Percival and Bennett were meeting. Twenty minutes later, three planes appeared and attacked the house. Many bombs were dropped, and I found a depression to squeeze into. It was scary to hear the bomb breaking through the trees surrounding the house and exploding so close to me. One landed a few feet from me with a thud, but did not explode! After the conference we were told that the road had been cut off by Japanese, but Bren Carriers opened the way for us to return to Singapore. Our C.O. decided he wanted a tent pitched, so four men were detailed to erect a white tent in the green expanse of the Gardens. We were seen by a spotter plane which directed mortar bomb fire on to us. I was struck on the back of the head by a fragment of steel. Luckily, I had put my chin strap at the back of my head, and his softened the blow. I didn’t hear it, but bled a lot and we did not proceed with the tent. On Sunday the fifteenth of February, our C.Q.M.S came to our trench, and said “It’s all over, we have surrendered”. I was thunder struck! I had been prepared to be wounded or even killed, but was totally unprepared for this. I hadn’t been prepared for victory after I heard that Major Kerr, of the 2/10th Field Regiment, had been ordered to cease fire on Johore Bahru, after the Nips had moved in to that city.

I had lived in the ute, and had been able to act as a Don R. when the motor bike chaps had been sniped at from the side of the main roads. I had been able to deliver hot meals to one of the battalions, when their cooks had been unable to produce because of the conditions, and it had provided shelter when a sniper had tried to get me at Tanglin. So it was with reluctance that we put sugar in the petrol tank, and it was handed over to the Nips.

We marched from the Gardens to the Selarang Barracks at Changi, with some of our own provisions for a few days; then we began our diet of rice and very little else. Our first task was removing barbed wire from the beach with bare hands, and scrounging what we could for the kitchen. We were short of fresh water, so used sea water to cook rice and were able to smuggle in, in the buckets covered with palm leaves, some coconuts, which the kitchen used.

In May 1942, we were driven from the Changi camp to the docks, to await transport to a destination of which every one seemed ignorant. Rumour has it that we were to be exchanged for Japanese P.O.W.s, in a neutral area! Here we found out that the Nips weren’t really nice. As we sat on the wharf, we could see that there were lots of goods in the shed. One at a time we were able to crawl under a truck, into the shed, and grab something and get out quickly. There were six in our little group, so singly we went in. I was early in, and in the gloom, grabbed two boxes and got out. One was tobacco, the other mustard. I don’t smoke, and we had nothing to put mustard on. One of our chaps was seen and beaten with a stick, but we were not searched. After sitting all day, we went on board at night, and found the holds were in terrible condition, with about half a metre of boards for each person. Toilets were box-like affairs over the side of the ship, and we used the ships hoses to keep ourselves clean. Meals were rice and a watery type of stew made mostly of tinned vegetables taken from the wharf. The ship called at Medan and took on board Dutch P.O.Ws. Next stop was Point Victoria where about 1000 men were put ashore. We landed our next party at Mergui, then sailed on to Tavoy, where our party went ashore, and we slept in a rice mill, which was a great change from sleeping on deck on “Toyahashi Maru”. Next day we marched about twenty miles to the aerodrome site and slept on stones in a hangar. We were allotted to huts and began work extending the runway. We worked 8 or 9 hours each day, wet or dry. It was from here that eight men of the 4th Anti Tank Regiment escaped but were brought back and shot. I had washed what clothes I had, when a Nip soldier came into our hut, and pointing said “You, you and you, come!” These men had to dig the grave for the executed men, and were very shaken.

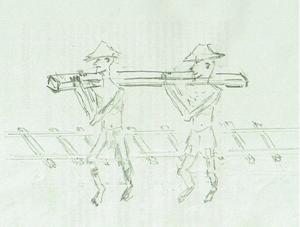

In September 1942 were shipped to Moulmein, and for the next three years worked on the Burma Railway. When we left Sydney, my wife was pregnant and I worried for two years, before I had word that she and our daughter were well. Our first task was carrying soil to build up the level of the line. We were told that moving a certain amount each day allowed us to return to the camp. This was a test, and the amount was increased tremendously over the next weeks; anyone not working to the guards’ satisfaction would be bashed about the head and shoulders. As work progressed on the railway, rations became scarcer, and sickness more frequent. I met with my younger brother from the “Perth” at Tanyin (35 Kilo Camp), and we managed to stay together for some time, until he became ill, and was left at the hospital camp. We worked from daylight until one hour before dark, working on bridges, and digging cuttings for the evenness of the line. We knew the camps only by “30 Kilo Camp” or “50 Kilo Camp”, and it was here I had pellagra, many men suffered from lack of vitamins, leading to beri-beri and other diseases. It was at a camp (18 Kilo) called Hlepauk, that we had the first of many deaths. Where a few drugs could have saved a life, following a simple operation, the little the doctors had, were taken by the Nips, leaving our troops helpless. Appendicitis meant death, tropical ulcers led to terrific suffering and amputations. In one camp we lost five men in a day from cholera; malaria became black-water fever; malnutrition and dysentery claimed many lives. The doctors were heroes in these situations.

From the 70 Kilo Camp on, Malaria became more prevalent; I had 34 attacks, plus 3 more after discharge. The Jap engineers were becoming impatient, and the guards were forcing sick men out to work despite our doctors protestations. We were working 16 to 18 hours a day, often having to return to our camp in pitch blackness, pouring rain and feeling our way across the framework of bridges, 30 feet in the air. On one occasion, with another ten or so sick men, I was forced to go to the railway after midnight, to bring supplies to the camp. In pouring rain we carried 35 bags of rice (240lbs. each), baskets and bags of rotting vegetables up 50 yards of slush to the road, a 45 degree angle making progress nearly impossible. It took four hours of “Speedo speedo” before we returned to our sick bays.

While driving piles for the railway bridges, eight or ten men would be pulling on ropes, while standing up to our waists in the river. The guards had a kind of chant, “Ichi nee nesarnya:, and we would let the ropes go making the dolley drive the pile a little further in to the bed of the river. Our own version of the timing was “Tojo is a bastard” which could not have been understood, but if the pile took too long to be put in place, we had “Speedo speedo” yelled at us; we were bashed, and a piece was sawn of the top of the pile to make it level with the others.

On more than one occasion, a pile was placed on top of a half submerged pile and another fastened to it with spikes. Small wonder we were not keen to travel by rail, especially over bridges. As the base of the line was laid, the rails and sleepers followed quickly. The sleepers were mostly heavy teak wood, and many men suffered from strains. I believe that it was this work that gave me the hernia, which still bothers me. When the sleepers were laid, bogies carrying the rails were backed up to that point, and the rails run off. The rails were then squared with crowbars, and spiked into position. Ballast was obtained by travelling at night to a dump some miles away loading it into rail trucks by hand, returning to the nearest work, unloading the stones, and packing it between the sleepers with shovels. At daylight we would be finished and sent back to camp sometimes to eat our rice and go back to work laying more rails.

On more than one occasion, a pile was placed on top of a half submerged pile and another fastened to it with spikes. Small wonder we were not keen to travel by rail, especially over bridges. As the base of the line was laid, the rails and sleepers followed quickly. The sleepers were mostly heavy teak wood, and many men suffered from strains. I believe that it was this work that gave me the hernia, which still bothers me. When the sleepers were laid, bogies carrying the rails were backed up to that point, and the rails run off. The rails were then squared with crowbars, and spiked into position. Ballast was obtained by travelling at night to a dump some miles away loading it into rail trucks by hand, returning to the nearest work, unloading the stones, and packing it between the sleepers with shovels. At daylight we would be finished and sent back to camp sometimes to eat our rice and go back to work laying more rails.

The 80 Kilo Camp (near the Apalon River) was a horrible place. So many died and were buried there. The position of the camp was badly chosen, as it was divided by a wide, steep gully. When a man died he was wrapped in a mat, we could not afford to use a blanket, and carried from the hospital, down one side of the gully, and up the other, making numerous stops as the bearers were too weak from sickness and malnutrition, to make it in one go. The Last Post was sounded, more often each day as the weeks went by, making everyone depressed. The Nip engineers could not have cared less about our feelings, and we were driven harder, preparing the way, and laying the line, as we grew weaker, each day seemed longer, and work became harder. While trying to join some points, the N.C.O. in charge of our party could not understand the Nips orders. The Nip flew into a rage, and as I was nearest to him, I was bashed on the neck and shoulders with some wire he was holding. We worked from 6am to midnight under pressure to finish the line and in mid October it was done. I didn’t see it as I was down with malaria. We spent some time at Niki, then were taken by train to a “Rest Camp”, Tamarkan. We were made to work, taking food to the lookout post on the hill, or working in the ack-ack post behind the camp. It was here the Americans bombed our camp, killing 14 British soldiers. Men’s nerves gave way after this and I can still hear the rattle of bamboo slats, as scared men ran to their slit trenches at night, when bombers flew over.

We could hear more frequently, bombing nearby, as the war went our way. One place that received most attention was the Wampo Bridge, and no one wanted to go there. After the Tamarkan Bridge was attacked, we were set to build a second bridge, just below it. When some unexploded bombs were found, we had to dig them up and take them to the river, where they were dumped. No one was injured, but it was a hair raising job. The guards were becoming very jumpy, and when air raids threatened, everyone had to race back to c amp. Here, after a raid, some of our chaps were struck by bullets, and I was able to give blood, but the Dutchman died. I was given an easy job, going to the town by barge to collect provisions. The Kluang (Muang?) camp also did the same. One of their guards took a dislike to me. One day when I left the hut to wash my shirt, he called me back, and said that I was trying to escape. Our guard was in the town, so he stood me up, with his bayonet poked into my bare back, waiting for an opportunity to push it through. I sweated for half an hour, until our guard came back and believed me. One day, at our camp, the Nip cook had received fresh meat, and took the baskets, covered in blood, to be washed. I had to lift these heavy things, (I had just bathed) and said something about the bloody baskets. He misunderstood me, and I was bashed for that. When the river was in flood, a boy fell from a canoe in midstream, and I was able to save him. His family showed their appreciation by bringing fruit and vegetables to the hut. The Nip guards took them. Following a raid on the Wampo Bridge, a work party was sent there. Of course I was on it. It was not hard work, but nerve-wracking, as we were bombed from time to time, luckily being able to find shelter. The shortage of fuel meant work parties were needed. I was sent with a party of 12, under a W.O., with an R.A.P. Corporal as medico to Cre? Here we felled trees, and cut and split them into metre lengths, and carted them to the railway line. Malaria bouts became more frequent and I believe that I would have been buried at Cre, if the war had not finished. On August 20th we were taken to Tamuang, and forgotten. About a month later we went to Bangkok, and on to Changi, then home.

EPILOGUE

The doctors I remember were:- Captain R. Richards, Major S. Krantz, Major Hobbs, Captain Andrews, Major Chalmers, and a Major I saw at Kluang, who I believe came from Newcastle.

Sickness. I believe the mortar splinter on the back of my head was a war wound.

Whilst P.O.W., I suffered, as did so many others, Pellagra, Beri-beri, Tinea, Malaria and Dengue Fever, Ulcers on my leg, Diarrhoea and Dysentery, Arthritis, Hernia, Nervous tension regarding our future, concern about my wife and family at home, concern for my younger brother, who had been badly wounded on “Perth”, and whom I had been able to help by scrounging and cooking meals for him.

AFTERTHOUGHTS

Keeping a diary as best you can, with the knowledge that a surprise raid on your hut could mean the discovery of that diary, and a bashing if the guards interpreted it, and took exception to something you had written, meant that references to them or the Jap army, had to be very low key. Unfortunately I have kept it at such a low key that I can’t remember what I was referring to, in many cases.

I remember going from our barracks to the gaol at Changi on work parties, and feeling so sorry for the internees locked in the main body of the gaol. Women and children would crowd the windows; we would wave and call to them, but the guards soon stopped us. We had no water for some time at the Gordon’s quarters, so any opportunity to go on a work party to the beach was grabbed. It meant a swim or a quick wash over with sea water. On occasions the tide was so far out, there were only mud flats to walk on, and no swims. One of the first water parties discovered five Chinese roped together and machine gunned, then left. There was nothing they could do, as the guard hurried them away.

Another thing that has stayed with me for all these years, is the smell of death throughout our march from the Gardens to Changi. Bodies lay where they had been shot, on the streets, and nothing had been done to remove them.

Among the things that puzzle me are:- Why did the British Engineers make such a poor job of blowing up the Causeway, after we had crossed to the island, and why was Major Don Kerr disciplined for firing into Johore, when the remnants of the Japanese Army were assembling there, prior to crossing to Singapore Island. Also, who was signalling from the Cathay building at night to someone outside the city? Harry Mills saw this, and reported it, as the Cathay building was being used as a hospital, with a large Red Cross on it.

Harry also saw orders from British Headquarters, giving details of retreats by Australian forces, well ahead of the actual dates. This may explain why our little party of Capt. Patterson, Robby and me, were left in a clump of trees at crossing of railway and road near Labis for three days without explanation or apparent reason. We watched the town and railway being bombed; a little pig farm about 200 yards away from us was destroyed, but our spot was untouched. I was greatly relieved when we were ordered back to our base at Johore.

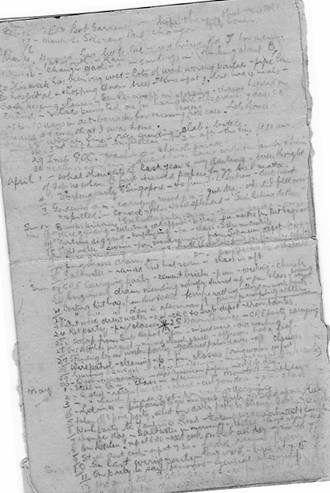

Pages taken from my diary – written in pencil, needing a magnifying glass to make it readable. Starts from February 15th 1942.

February 15 Capitulated Botanical Gardens – hope the news that we are OK gets home.

February 17 March to Selarang Barracks, Changi.

March 14 Dreamed I had little lad – red haired. Transferred “J”, for Administration. (Am not sure what this means, but CQMS Jim Stewart from No. 2 Coy and I were put in charge of rations, as the OC had complaints that they were not being fairly distributed).

March 15 One month since capture. Lots of rain.

March 16 Work party to Changi Gaol carting sandbags. Thinking about the worry Grace must be having.

March 20 This week has been very wet. Worked on taking barbed wire barricades on the beach. Bare hands. Work party laying pipe line to hospital

Work party chopping down trees for kitchen.

Thursday Up at 7am, but had four meals. (Can’t explain that).

Book keeping classes. (Gordon Weynton organised classes. As I had done some accountancy pre-war, I attended).

General Percival’s car stopping – chassis hitched on behind. (Have forgotten this one.)

Two lads punished:- One for having 1 tin of sardines, 2 days in lock-up. The other 10 days in detention for missing tattoo rollcall. Possibly outside the fence trading).

Lots of rice arrived at camp. Dreamt 3 times that I was home.

March 25 Weather fined up. Rice grinding duty – with bottle on slab.

March 26 Third Japanese inspection. First two in afternoon – this one 10am. (We lined the roads, and Jap Officers drove past).

March 29 Inspection by GOC (Nip) did washing. Church parade.

March 31 Nearly 12 months away. Dreamt I was home with family.

April 1 What thoughts of last year and my darling. Even thought of February 24th., when I first received papers to go to Parramatta.

April 4 Working party to Singapore. Best event.

April 7 Gardening party a.m. Carrying wood p.m. Good tea, which I spilled when I fell over. Concert at night. John Wood splendid; “Girl behind the Bar”.

Sunday 12 Eight weeks prisoners! Saturday water party and swim. PM Church parade.

Monday 13 Rice grinding. Collecting odd apparel and kitbag.

April 14 Latrine digging – emptying. Pm. Class – salesmanship!

April 15 Salt water party – swim. Pm. Wood carrying from Submarine Depot.

April 16 Rice grinding - using bottle and slab, flour for ?

April 17 Engineers drain am – pm paybooks to ?

April 18 Salt water party – rained but had swim. Class in pm.

Sunday 19 G.R.E. carrying party – cement bricks – pm/washing and church.

April 20 Engineers drain mending party – nobody turned up. PM class and evening --------Concert?

April 21 Carting kitbags from Div. to AOC. Terrific ratting Lloyd on work party. PM. Pumping water.

April 22 Carting kitbags am pm class

April 23 Wood cutting – pumping water. CRE to Sub Depot collect iron tanks.

April 24 Kit party AM. Classes PM

April 25 Dawn Service – CRE party carrying attap from Sub. Depot. PM missed work – did washing.

April 26 8.15 kitbag picquet. – mixed church parade. Afternoon had a loaf.

April 27 Standing by on work party – gathered palm leaves. PM classes.

April 28 Wire patrol! Cleaning up beach. PM Classes. Ringworm on foot.

April 29 Learning CQMS job. PM classes – concert at night (Mo. McCackie).

April 30 Q job – collected rations. Read US papers most of the day.

May 1 Still on Q job. Class in PM. Month of birthdays.

May 2 Q still rations from ASC. Cut goons down. Classes in PM.

May 3 Q party. Church parade 9.45. PM wash & darn.

May 4 Latrines – preparing to go Singapore work party, (take lunch).

May 5 Taken off S’pore party. Sent on daily party to Changi Gaol.

May 6 Work party to Tampines Road. Tea – Camp Pie and Sauerkraut, cauliflower.

May 7 Donga day – salt water in am. Rested pm. Heard about ?.

May 8 On kitchen! Up at 6.30 assistant cook – on feet all day – finished 7 PM.

May 9 Still asst. cook. Up at 7.30 heard rumour of going trip.

May 10 On last wiring party. Long walk – back at 7.15pm.

May 11 On party to sail tomorrow – general clean up.

May 12 Not going till Saturday. -----?. Allotted to 4 Section, No. 14 Platoon ------?

Wed. 13 Parade – hear we are off at 7 tomorrow. Last concert party.

May 14 Last day in Malaya. Left Changi 8am. On board Singapore wharf – midnight.

May 15 Left Singapore – pulled out 11.30 sailed 2 PM. Direction North West.

Continuing saga aboard “Toyahashi Maru” 1942.

May 16 Still North West. Loading party standing by.

May 17 Arrived Medan (Sumatra). Loading party still standing by (Palawan) Read “Popinjay”?

At this stage, I must say that we had been told we could be heading for a neutral port, where we could be exchanged for Japanese prisoners! That was why the direction was important to our high hopes.

Sun May 18 Dutch Army Officers arrived – Pulled out 7.45pm. Saw beautiful mountains – smoke stacks – 3 other POW ships apparently.

May 19 Fairly choppy sea – heading North. Read “Hippy Buchan”.

May 20 Saw numerous islands – mess orderly – arrived Victoria Point 4PM.

May 21 At anchor – bit off colour (stomach). Approx 1000 men and stores sent ashore.

May 22 9.15am. Moved north then West, through hundreds of little islands – then headed north.

May 23 First fatigue – hosing toilets and deck. Up at 7 AM. No water until 10 am. Tasted Jap food. Arrived 1pm Mergui. Lights at night. 4.30pm. Cold in head.

May 24 Shaved – still at Mergui.

May 25 Sailed 8am. Arrived Tavoy late evening.

May 26 Went ashore – small boats. Left 6pm. 2 hour hike – tea. Slept at rice mill.

May 27 March to Tavoy aerodrome – 22 miles in 11½ hours – very stiff – Archie had taken tea from Jap truck – near blackout – very sweet black tea. March 1½ miles to hangars. Slept on stones.

May 28 At aerodrome – up 0830. P/T very wet day no morning or midday meal.

May 29 Work party – many jobs – finished 7.30pm.

May 30 Off colour – no shower – no work – no food.

May 31 Still off colour – rained – got clean

June 1 Better – water carrying – shower in rain.

June 2 Line carrying (for skips) milk for lunch – marvellous, first in 3½ months. Heavy rainfall.

June 3 Clearing out huts for us to move -

June 4 Moving dirt on drome – petrol in ---? Gear arrived, moved into huts – 1st day no rain – good sleep.

June 5 Pick and shovel work a.m. wire carrying p.m. Did washing – thought of Grace and baby?

June 6 Drome work – rain – rottenest fatigue party yet

Sunday 7 Off day washing – church parade – carrying rations.

June 8 Erect petrol stand – moving petrol

June 9 Petrol again – First plane arrived

June 10 Petrol – Allowed to write two letters (Grace & Mother)

June 11 Drainage work

1942 At Tavoy – lengthening runway

June 12 Cleaned up hangar & rolled petrol

June 13 Petrol into hangar all day

Sunday 14 Church Parade – washing – No rest until p.m.

June 15 Petrol in a.m. Loading skips p.m.

June 16 Petrol in a.m. Wood collecting p.m. – donga

June 17 Rolling petrol all day

June 18 Petrol all day

June 19 Light duties – rice grinding

June 20 Carting skips of dirt – resting p.m.

June 21 Guard duty all night!

June 22 Rest day after guard duty

June 23 Shovel and empty skips

June 24 Move earth with chungkol and shovel

June 25 Shovel and carry earth

June 26 Breaking stones

June 27 Move earth in skips

Sunday 28 Church parade – washing – Rest p.m.

June 29 Moving earth all day thinking of Grace

June 30 Shovel for Dutch?

July 1 Skips all day – fill with earth, then push to other end of runway

July 2 Skips again

July 3 Shovel for Dutch?

July 4 Permanent skip party

Sunday 5 Church – rest day – sugar and salt turned up, also bread

July 6 Skips – good meals

July 7-8-9-10 All same work

July 11 Skip work – moved line

Sunday 12 Church – washing – Fritz birthday? Concert PAY DAY

July 13-14-15-16-17-18 On skips every day

July 19 No church – did washing – made jam! Read.

July 20 to 26 Skips

July 27 Lousy and cold – off work 28-29-30. Thought of last years goodbyes especially Sunday. (We had lunch at the California, in Kings Cross. Left Sydney on 29th.

July 31 Back at work. Skips.

August 1 Skips

August 2 Sunday – washing and rest.

August 3to8 Skips. Torrential rains washed away large part of what we had moved: so we did it again.

Sunday 9 Church parade – washing – mended boots – cooked and read

August 10-15 Work on skips.

August 16 ?

August 17 Rest

August 18-22 On skips – finished job. B’Day 21st.

Sunday 23 Church – laundry – football – concert

August 24 Cutting timber

August 25-29 Back again on skips. West side of runway – making N/S and E/W landings

Sunday 30 No church – too wet for washing – read – concert

August 31 Skips

Sept 1 Skips – new shift 2 to 7pm

Sept 2 Skips

Sept 3 Skips – Anniversary of war

Sept 4 Grace’s birthday – skips

Sept 5 Skips

Sunday 6 Wet – read

Sept 7 – 8 Afternoon shift on skips

Sept 9-12 Morning shift from 9 to 2

Sunday 13 Wet – read (Damon Runyon book – good for swap)

Sept 14 Skips am

Sept 15 Skips am. Cleaning up pm

Sept 16 (Demolished shed – pm off) see page 42 “Slaves of the Son of Heaven”

Sept 17-19 Road making

Sunday 20 Church – washing

Sept 21 Road making

Sept 22 No work – told of move to Rangoon

Sept 23 No work

Sept 24 Work in morning

Sept 25 No work – soccer match

Sept 26 No work

Sunday 27 Church – washing

Sept 28 Packed our gear

Sept 29 Left Tavoy – 1pm. 5 mile march to wharf – barges wharf 4.30. Reached ship 9.30. 500 men in forward hole of 800 ton ship. Heat terrific. About 2am got up on deck and slept. Often stood on being in the way. At intervals we ate some of our previously cooked food, and old biscuits. At 8am “Unkai Maru” set sail.

Sept 30 Sailed north – kept close to land, speed about 8-9 knots. Sat on deck – ate more biscuits – slept on deck on green box.

- Moulmein and the Burma Railway

Oct 1 Came into Salween River, reached Moulmein about 1pm. Berthed at 3pm. No.14 Platoon had to clean up. Marched thru city to a church, about 3 kilos. Slept in church grounds. People here were very good, handing us food as we passed – even soap. Had tea and a good wash.

Oct 2 Up at 7.30 – packed and ate. 8.30 moved back to train. Open truck seating 36! 40 mile trip to Tanbou something. (Thanbyuzayat), arrived at 1pm, moved into evacuated huts. Cleaned up and slept!

Oct 3 Cleared path – did washing – numerous washes at well to clean dirt of previous days. Slept well.

Sunday 4 Church parade – fatigue party clearing path.

Oct 5 Began work – sprung on us. Walked about 2 miles. Moving earth – one each end of bamboo pole, rice bag full each trip – finished 7pm. Camp about 8pm. Rotten day.

Oct 6 Same work – late finish. Near native village. On guard night 2/3am.

Oct 7 Same job – finished 5.30 (moved pegs). Meals rice and stew.

Oct 8 Reveille 7.30 – same work. ?8 – parade 8.30, get to work about 10. Night Dutchman?

Oct 9 Same work – tipping bags of earth – bought moublas (like pancakes) finished 5pm.

Oct 10 Packed up & moved. Marched about 15 miles, arrived 10pm. Rained – bathed.

Sunday 11 Church parade – cleaned up – built hut.

Oct 12 Work – about ½ mile in cutting – bag and pole – 9 to 5. Creek to wash in!

Oct 13 Same work – heavy rain at night.

Oct 14 Hard day 9.30 to 6.30 wet – small area. (I think we moved our boundary pegs again).

Oct 15 Mess orderly – same work.

Oct 16 & 17 Same work – rain every day.

Oct 18 New area – easier work, despite Sunday. Church at night.

Oct 19 Same work – longer lunch hour, signing papers saying we will not attempt to escape. (Duress)

Oct 20 Moving dirt 9 to 6

Oct 21 Day of washing and cleaning. Had shave, rest & played cards.

Oct 22-25 Same again – poles & bags, moving earth, easier soil.

Oct 26-27 Same work – gave Padre razor for barber.

Oct28-30 Same work – heard Gavin may be in next camp, didn’t believe it.

Oct 31 Note from Gavin (Ian’s brother Lt RAN Gavin Campbell-Survivor HMAS Perth). No rest day

Nov 1-2 Same work – trying to find some way of getting to see Gavin

Nov 3 Rest Day – 1st in 10 days. Shave & haircut (bald)

Nov 4-7 Bag and pole work.

Sunday 8 Work – church after tenko

Nov 9 Moving earth – same work

Nov 10 Letter from Gavin

Nov 11-14 Same work. Rained 13th. 14th. Shaved 6 chaps

Nov 15 PM rest. Patching clothes

Nov 16 Digging drain – injections for cholera, in arm.

Nov. 17-19 Same work – drains & shift earth. 18th. Received letter from Gavin. Bunty Drany arranging for me to take his place on cattle party. The QX-rs handled the little meat we had.

Nov. 20-23 Still digging and shifting. New Korean guard arrived. Poor type.

Nov. 24 Took one nastly little miserable steer to TANYIN. Met Gavin. No hair, wearing flour bag. GREAT DAY.

Nov. 25 Rest day and church.

Nov 26-28 Back on bag and pole

Sunday 29 Work day – church at night. Hair cut.

Nov. 30 Same work on embankment.

Dec. 1-2 Same work. Pm. Well digging

Dec 3-4 Same work bag and pole.

Dec. 5 Rest day – very windy – letter from Gavin

Dec 6 Same work – church service new Padre.

Dec 7 Hard work – plodded back – Larry Oakeshott (SX7041) very ill (Appendicitis)

Dec 8 Work as before – Larry died.

Dec 9 Day off – bad back

Dec 10-11 Back at work – letter from Gavin

Dec 12-14 Work on embankment

Dec 15 Day off! Cooking – wood party

Dec 16-18 Moving earth. 17th. Had bubonic plague inoculation sprung on us. Guards very lax – work easier.

Dec 19-21 Same work – meals better. 19th. Had 1st start in meat Derby. (After the cooks had taken every piece of meat and fat from the carcass, the residue was placed outside the cook-house in a drum, and anyone who thought they could get any use from the leavings were welcome to try. I had a small tin and would take a piece off the intestines, to scrape a piece of fat about the size of a little finger nail and then try to get more fat to melt down. I would put Gavin’s and my rice into a pan, made from a plate and dry out the rice, at the same time giving it some flavour. Gavin said that saved his life

Dec 22 Work on bags & pole – moving earth – guard called little Boof. (Was not game to refer to guards or anything Nipponese, as we risked a bashing if records of their treatment was written. I wrote! Little work! With boof after it).

Dec 23 Worked on well sinking.

Dec 24 Still on well – mixup re case! (Harry Mills sold a silver cigarette case to a guard. Harry promptly bought food with the money. The guard then said the case wasn’t any good, and demanded his money back. Harry didn’t have it, so asked the interpreter, Capt. Bill Drower, to explain to the Nip, (incidentally, a professed Korean Christian). The Nip put on a turn, bashed Capt. Drower, and stirred the Australians up so much that they were prepared to take on all the guards. Colonel Anderson intervened; and things gradually cooled down. We then went to work, but I still wonder what would have been the outcome, if Colonel Anderson had not stopped the near riot.

Dec 25 Christmas Day! Good meals – the cooks – Syd. Clerke (NX60095), Lionel Oldman (VX28508) and Jimmy Campbell had put aside a little bit of the ration each day to make a good dinner. We had a piece of meat each, with rice, a sweetened rice ball, and a biscuit. It was so different from what we have eaten for the previous year, that it was a real treat. We had church and a concert at night.

Dec 26 Back to work again – pole and bag, moved earth.

Dec 27 Worked at erecting tents. Received Post Cards thru Red Cross. 5 cards.

Dec 28 Finished work with tents.

Dec 29-31 Back to finish year’s work on pole and bag on the embankment.

1943

Jan1 Day off work – good meals – church parade & concert at night.

Jan 2 Up mountain for timber – felled, trimmed and slid down to the embankment; hard work but I remember that we could see the sea in the distance.

Jan 3 Moved to 35 Kilo Camp. Amalgamation of Colonel Williams and Colonel Anderson’s forces into “A” Force. Joined up with Gavin. Wonderful day.

Jan 4 Day off. Talked most of the day.

Jan 5 Another day off. Shaved 6 or 7 chaps.

Jan 6. Work began - 1½ mile walk back to job. Long day – finished about 6.15pm.

Jan 7 Same work – finished 7pm

Jan 8 Day off – Gavin’s leg sore. I stayed home too!

Jan 9 Work again - 1½ mile trek to job.

Jan 11 Day off – rumours of scurvy

Jan 12-13 Clearing playing field – 10 Kumichos put in charge of Kumis (each 40 men) Officers only.

Jan 14 Rest day – great talks with Gavin

Jan 15-17 Work 2½ miles from camp

Jan 18-19 Embankment work – bag and pole moving earth

Jan 20 Cattle party to 18 Kilo Camp – very tired – long walk.

Jan 21-22 Days off

Jan 23 Digging work

Jan 24 Rest day

Jan 25-26 On embankment

Jan 27-28 Days off. Mother’s Birthday

Jan 29-31 Still off. Malaria – felt rotten

Feb 1-2 Malaria

Feb 3-4 Light duties in Camp (Kitchen)

Feb 5 Rest day

Feb 6 Back on shovel – now 1.6 cubic metres each man

Sunday 7 Worked again - ½ day off for food (or foot-tinea?)

Feb 8-9 Work on bridge

Feb 10 Day off with G?

Feb 11 Rest day

Feb 12-14 Work on bridge. 6am – midnight (or later)

Feb 15 Rest day

Feb 16-19 Bridge work. All day in river driving piles.

Feb 20 Finished bridge. If piles stuck on river bottom – sawn off and left. If piles too short, another pile attached with 4 or 5 spikes.

Feb 21-23 Digging at 29½ Kilo mark.

Feb 24 At 29 Kilo mark – still on embankment

Feb 25 Gavin’s birthday – rest day – little cake – 22 NUTS

Feb 26-27 Work at 29 kilo

Feb 28 Day off – Gavin’s foot sore.

March 1-2 Work at 29 kilo peg – Americans bombed Thanbyuzayat

March 3-4 Work at 30 Kilo

March 5 Rest day – Weighed – Gavin & I both 11.2

March 6-8 Work at 30 K peg. Lunches with Gavin.

March 9-10 Finish at 30K.

March 11 Work at 36 Kilo

March 12-15 At 36 Kilo Camp

March 15 No rest – Gavin off with bad throat. Had swim.

March 16 Resto! Cooking – lots of porridge

March 17-18 Finishing off jobs

March 19-23 Working at 36K with Gavin

March 24 same

March 25-27 Still on embankment

March 28 Worked till 2300 – rather fun! (I think this is where we built a framework of branches, then filled in the spaces with earth.

March 29 Up at 0345 hrs. March back to 25K camp. 2 blisters

March 30 Rest day. Rested

March 31 No work

April 1 Second anniversary

April 2-3 No outside work – camp fatigues

April 4-5 Digging drains and cattle. (We had done enough work on the embankment, and were ready to start on the placing of the railway line).

April 6 Sleeper work – 5 sleepers – finished at 11

April 7 Dog spiking at 18K. peg. Finish 7pm

April 8-10 Carrying sleepers at 30K. (36)

April 11 Sunday Rain – no work. Wired soles of boots to uppers

April 12-13 Sleeper carrying at 35K peg.

April 14-17 Put in siding at 30K. Vaccination for smallpox

April 18 Day off – gastric. 19/20 still off – made jam!

April 21-22 Still off

April 23 Gavin had day off – heavy rain

April 24 Prepared to move. 8.30am. waited till 9pm. Comic move? Can’t remember. Worked till 2am.

April 25 Anzac Day – started work on rails – worked till 3.25am. (rails were run off bogies, onto sleepers – then spiked into position by measure).

April 26 Thoughts of this day in Sydney – Easter Monday.

April 26-27 Rail work on laying the line.

April 28 Bruised foot, day off, had swim.

April 29 Work – despite Jap Emperor’s birthday.

April 30 Work on sleepers

May 1-6 Touch of fever – feeling pretty crook. Quinine treatment.

May 7 Feeling much better. Japanese medical inspection, sent to work!

May 8 Moved to 60 Kilo peg.

May 9 Mothers’ Day – work – water carrying.

May 10 Carrying sleepers

May 11 No work

May 12 Carrying sleepers again. Heavy work.

May 13-23 Worked from 47K to 60K packing sleepers, from reveille 7am to 9pm. No shave! (That means something – can’t remember what). Rain set in worked thru it. Thought of Dad and Don’s birthdays 14 and 18th.

May 24-25 Same work – came home sick.

May 26-29 Work on ballast – tree felling and bridge work.

May 30-31 Sick – diarrhoea.

June 1 Fever

June 2-4 Off sick – Gavin also

June 5-7 Back at work – bridge work

June 7 Gavin moved to 40K camp – woe!

June 8 Very wet – still worked.

June 9 Tom Dwyer died. Lovely chap – station master! First cholera case – all went to funeral.

June 10 No duties

June 11-13 Light duties

June 14 Work again – road work at 66K after rain

June 15 Bupin. (Kitchen). Wood carting

June 16-19 Work on road

June 20-23 Bupin again. Wood carting. Notes from Gavin

June 24 Malaria again. (Had a mixture of fevers, dengue and malaria)

June 25-30 Off sick – on 29th. Jolly old anniversary – all the very best for many more darling. Feeling better. 30th. Still off – thought of Kurrajong.

July 1 Still sick

July 2 Gavin returned – Great!

July 3-4 Still off – great chindegar incident. Caught by guards in Coolie hut buying sugar. Thought I was going to be shot for escaping!

July 5 Light duties. Did nothing, plenty talk.

July 6 Back at work – previous week. All early finish – today spiked all day until 8 PM.

July 7 Spiking rails

July 8 Collecting spikes – no dinner

July 9-10 Bupin again. Got water for rice cooking. Kept fire going. Prepared vegetables? Chilis & Hairy Marys washed kualis and poys.

July 11 Fever again

July 12 Bed

July 13 Move to 70K camp – rotten day

July 14 Off – everybody given work – malaria

July 15-18 Still sick – leaking roof. (Attap) very wet.

July 19 Moved into new hut

July 20 Gavin and I talked a lot

July 21-23 Light duties. Ration party at night. (Referred to in “Slaves of the Son of Heaven” on page 85. Nearly killed me. I remember lying in hut completely exhausted. Some insects in the attap chewed away, sending tiny pieces on my face. Rain poured thru the roof, so I sat up the rest of the night, wet and cold, and covered in sawdust.

July 24-25 No railway work – ration party

July 26-29 Laying sleepers and lines (Branded B.H.P.!)

July 30 Move to 80 Kilo Camp. 10 Kilo walk

July 31 On line again – we handled 47 trucks

August 1 Leg poisoned – tropical ulcer – day off

Aug. 2-5 Off with fever and leg. Gavin off with Beri-beri

Aug 6-8 Malaria

Aug 9 Light duties – mess orderly

Aug 10 Light duties – cook house

Aug 11-12 Off with Beri-beri

Aug 13-16 Still Beri- beri. Gavin moved to 55 Kilo Camp (Hospital Camp- CO Lt Col Coates)

Aug 21 29 today. I know I will be thought of. Weight 90½K 9.8

Aug 22-24 On Atebrin treatment

Aug 25-26 Still off

Aug 27 Back on rail – day work

Aug 28 Night work

Aug 29-31 Sinovitis – No duties

Sept 1-3 Still off

Sept 4 Bun’s birthday – next year Bun. Moved to 95K (Kyandou) camp

Sept 5-6 No work – settling in upstairs, 1st day. (2 levels in hut). 16 to a bay. Meal of rice and condensed milk.

Sept 7-9 Injured knee – no work

Sept 10-11 Off work – can’t walk.

Sept 12 Moved to 108 Kilo Camp on sleeper trucks

Sept 13 No work

Sept 14-16 Malaria

Sept 17 Move to 116 Kilo (near Kami Somgkurai) camp. 4K by rail – 4K on foot. What a camp. Saw Fritz on way. Note from Gavin. Just lay down in the mud and slept.

Sept 18 Settling in – miles of mud – rebuilt huts – bamboo and attap. Bea’s birthday.

Sept 19-20 Last days off

Sept 21 Back to work. Move to 122 Kilo (between Songkurai and Shimo Songkurai) camp

Sept 22-23 Work all night – finish about 4am. Up again at 8am.

Sept 24 Work spiking. (Can you guess how hard it is to drive spikes in pitch blackness – with a light from oil in bamboo holder! We copped many bashings here).

Sept 25 Bad feet – no boots. Off work.

Sept 26-27 Work night work on rails

Sept 28 Work again, day work I think.

Sept 29 Move to 131 Kilo (Little Niiki) camp. No roof on hut.

Sept 30 Night work. Speedo speedo!

Nike and completion of railway line

Oct 1-2 Night work on rails

Oct 3-4 No outside work – erected tents

Oct 5 No work – waiting for rails and sleepers

Oct 6 Carrying sleepers

Oct 7 Work for “Storm Trooper”

Oct 8 Malaria (Fever C962)? That could be

Oct 9 62?

Oct 10-11 Fever again. No duties

Oct 12-17 Still off Beri-beri this time.

Oct 18 Rail connected at 153 Kilo peg – I wasn’t there.

Oct 19-23 Still off sick. Worked in kitchen

Oct 24-27 Work two days then rest day – I wonder!

Oct 28 Ration party. Ten men were marched by guard to store about ½ mile – then brought days ration back to Jap cookhouse and our cookhouse.

Oct 29 Ration party again.

Oct 30-31 Fever – no duties.

Nov. 1-6 Still off with fever.

Nov 7-8 Light duties – building and moving new kitchen

Nov 9-10 imps? Off railway. Heavy rain

Nov 11-12 No work – afternoons building new Nip hut

Nov 13 Latrine digging

Nov 14 Carrying logs for store

Nov 15 Hygiene party!

Nov 16 Repairing bridge (Possibly between camp and store)

Nov 17 Latrine digging

Nov 18 Ration party – saw “F” Force Sigs from Bangkok

Nov 19-21 Off with fever – concerts in afternoon and night. Very cool.

Nov 22 Pretty -----------------------? (Should have done this years ago)

Nov 23-24 Well again – note from Gavin

Nov 25-27 No duties. On ration party

Nov 28 No duties

Nov 29 Ration party – Pomillo? (Either bought or borrowed from Nip kitchen)

Nov 30 No duties – Beri-beri again.

From Nike to Tamarkan

Dec 1-3 Beri-beri. No duties

Dec 4-5 No outside work – worked in kitchen

Dec 6-7 Kitchen – marked IC. (What?)

Dec 8-15 Rotten fever

Dec 16-17 Better

Dec 18-19 No duties. MEAT.

Dec 20-22 No duties

Dec 23-24 Sick parade – bad feet

Dec 25 Christmas – missed everyone. Meals fair

Dec 26 Moved to 133 Kilo camp (Nike). Had letter from Gavin, 23rd. Marvellous news about letters from home.

Dec 27-28 At Nike. No duties – bonzer river – decent huts.

Dec 29-31 No duties. Good weather. Bunty Drany – Don Taylor and I made tent of ground sheets and capes, slept in open.

1944

Jan 1 Festivities? Not like last year. (We wondered what was to be next work after a short spell)

Jan 2-3 Sleeping away from crowd in open seems freer.

Jan 4-6 Fever – not bad.

Jan 7 Sickish. Moved back into huts because of incident! Coming up from bathing in river, saw basket of pumpkins outside Nip cookhouse. Took one and hid it. Cook placed another basket outside with pumpkin tied to his big toe. Black Dutchman tries to take one about midnight. Wakes cook, who shouts blue murder and gives chase. Dutchman pounds past our tent with cook and guard in pursuit. Races thru Aussie hut and escapes. Next day we finished our pumpkin, and went back into our hut.

Jan 8 Feel better

Jan 9 QM again

Jan 10 No outside work

Jan 11 First party left for Kanburi

Jan 12 We move out

Jan 13 25 hours trip in goods truck. Two died. Passed over large bridge, past large camp, made Kanburi. Then 4K march back to camp beside bridge! Met Gavin.

Jan 14-16 At Tamarkan – many parades – counting (Tenko). Camp duties. Settling in to dry huts – rest from outside work. Even a canteen!

Jan 17-18 Ration party

Jan 19-20 Dodged? Q store and kitchen jobs – no go

Jan 21 Took rice water from cookhouse to make yeast.

Jan 22 Got job as coffee seller – issue cards to send home

Jan 23-24 Water carrier for coffee – set fires each night so that wood will be dry in morning.

Jan 25 Carted wood and water

Tamarkan – Kluang

Jan 26-27 Fever

Jan 28 Mother’s birthday – very feverish

Jan 29 Better

Jan 30-31 Fever again

Feb 1 Gavin has fever

Feb 2 Both better

Feb 3 Back to work – selling coffee. (My area took in part of the hospital – if I had any coffee over – 40 cups @ 10c each – I gave it to sick chaps)

Feb 4 Coffee selling – planes came over

Feb 5-7 Water carrying

Feb 8-12 Malaria again

Feb 13 Back to coffee selling

Feb 14 Promoted to coffee maker

Feb 15 Letters arrived from Grace and Jim Williamson. Wonderful news although two years old.

Feb 16 Coffee making spilt boiling coffee on leg!

Feb 17 Making coffee

Feb 18-19 Taking cash from coffee sellers. One chap asked for extra in his tin and we split the profits. Not on.

Feb 20-23 Fever – weighed – Gavin 83, me 70½.

Feb 24 Off work – bad leg. Concert “Ali Baba”. Excellent.

Feb 25 Gavin’s Birthday – bought duck! Strong winds blew hut down – no b’day cake.

Feb 26 No duties

Feb 27 Selling coffee – leg O.K.

Feb 28-29 Selling coffee – some very sick chaps

March 1-2 Still on coffee round. Concert at night.

March 3-4 Same job

March 5-6 Same – air alarm at night. I can still hear the rattle of bamboo slats as nervous men ran to the slit trenches. The ak-aks would open up, but the objectives were far away. No alarm as they return

March 7-10 Coffee selling – day and night alarms

March 11 Making coffee for a change 6am start

March 12-15 Cashier

March 16 Selling coffee

March 17 St. Patrick’s and Heather’s day – working on fires meant to celebrate but nothing available.

March 18-19 On fires

March 21 Day off

March 22-24 Selling on new run (officers’ huts I think, Bert Ricketts had job of purchaser for the officers).

March 25-31 Same job on same round. (Better conditions meant much less sickness all round. The Nips never understood this).

End of Diary at Tamarkan

1944

April 1 So many newcomers to this camp. We work two shifts. I was on morning shift – in new quarters.

April 2-19 Coffee making

April 20 Day off – planes over.

My diary ended here – we had another year and four months to go. I haven’t covered the best job I had – the barge parties to Kanburi. The move to Wampo Bridge, where no one wanted to go, because of the bombing. Move to Kluang where I worked in the Cemetery. Move to Cre? (Our guess – it may have been Gwe) where we fell trees and provided wood for the railway. We were there, a party of 12, with a Warrant Officer in charge, and a Medical orderly, with about 5 guards when war finished.

1944 TAMARKAN AND BEYOND

Now that the diary has finished, I have no idea of dates and times but places and things that happened are not easy to forget. As I said earlier, I always tried to work, and felt that working kept me going, and helped to keep my mind occupied. One of the jobs we shared with other nationalities was taking supplies from the Nip cook-house to the Nip observation post, on the hill behind our camp. Australians one day, British the next, then Dutch, then American, in rotation. We first worked around the cook-house, cleaning up, drawing water, and just before lunch time, carrying wooden buckets of rice and stew up a very slippery path to the post, collecting the used buckets, and returning to the cook-house to clean the pots and buckets. One day the Dutch party was returning just as an air raid began. The party ran towards the camp, and threw themselves on the ground as the planes came over. The Nips fired at the planes with machine guns, but were well astray, as one Dutchman, flat on the ground, had his water bottle, at his waist, hit by a machine gun bullet. On one of our days at the cook-house, a young private offered me part of his lunch. It was the first sign of compassion I had seen. I refused, as he seemed about sixteen or seventeen, and they didn’t seem to be eating much better than we did. Next day, three American planes bombed that camp, killing all in that area and landing one bomb in our camp, killing fourteen British POWs. It appeared that the planes let their bombs go in unison anywhere, and we also suffered. We dived for cover, and I found myself behind a tree about three inches thick, watching the grey smoke rise from the bombing, and dead scared that the planes that were swinging round would make another run. They didn’t, and disappeared the way they had come. We were on tenko parade at the time, and anxiously asked each other, “Ours or theirs”, ours being Nippon by now. The Dutch had shot through, and our officers called “Stand Fast”. This wasn’t easy to do, as the Nip ack-ack guns opened up, so we looked for shelter. On another occasion, an American plane attacked the lookout post, and came across our camp, firing cannon and machine guns. I lifted my head high enough to see two parallel lines of machine gun bullets going across our parade ground beside us. It was up for two seconds. We had tin hats on, as some of the Nip fire fell in our camp. This was when two POWs were shot and the doctors tried to get blood donors to keep the victims alive. Gavin’s blood matched one of the Australians, and mine matched the Dutch soldier. Unlike modern ways, we were asked to try to find other donors, so went through the huts asking for help. No coffee and biscuits. Gavin’s man survived, but my Dutchman died. It is hard to believe the ability to improvise that came to light in these days. A Dutch chemist, Bill Roberts from the Perth, and Plummy Kynvin, also from the Perth, made medical equipment from bits and pieces. That amazed the doctors. I worked for a while as slushy in the cook-house, cleaning all the utensils after every meal. It was rather tedious, but essential. A couple of our chaps, who were builders, organised working parties to bring clay from the river, and built a baker’s oven. With a mixture made of ground rice, rice water, and salt, little loaves were made, and served out to a portion of the Australians, each second or third day at evening meal. They were small and heavy, but we had not tasted bread since Tavoy, so it was appreciated.

Soon after this I was given a job on the provision barges that went to and from Kanburi. The barges had no motors, so were towed by a diesel powered boat; two at a time. There were some great chaps in this work party, and I became very ? with Laurie Blake, from Nagambie. When our barge reached Kanburi, we would meet the party from the camp at Kluang, and go by truck into the town to pick up supplies, everything being in baskets, meat, vegetables, fruit, tobacco and at times Mr. Boon Pong, the Chinese merchant would put a newspaper in as packing. When the first barges were loaded, one of us would go back with it, to make sure everything arrived safely, and have an early day. On one occasion, the man on the barge offered me his wife’s favors in exchange for a hand of bananas. I preferred the bananas! The Dutch unit forced an officer on the party (our highest rank was W.O.) and he soon showed his true colours. While waiting in the hut at the landing at Kanburi, he suggested that we could hold some provisions back, and sell them. He lasted one trip! As far as I know everything that was loaded for our kitchen arrived there. The Nip cook-house was different. We had to be fairly strong, to carry bags of rice and peanuts down a slippery bank, over a gang plank, on to the barge. When the river flooded, the trip became rather exciting, as we rushed toward Kanburi. It took a long time to return upstream, dodging logs and debris, giving us time to see the changes the flood waters did to the banks of the river. Deep wells became semi-circular holes, where the rush of water carried the soft soil away. Lovely kingfishers had their nest holes demolished, and sat forlornly on branches near the bank. We had never seen so many, and their colouring was beautiful. During the flood, a young chap was thrown from his canoe, we heard the cries of the people on the bank, so I got out of my boots and shorts in one movement, and was able to catch him about midstream. Tom Beenie (VX65487) dived in to support him, and he got only a ducking. I couldn’t come out of the water until someone handed me my shorts. I was still surprised to find my bootlaces still tightly tied. The people who had gathered were very pleased and next day brought lots of fruit for us, which the Jap guards took.

As I have probed deeper into memories of those days, I find I have had some missions in various events, when the time and the place eludes me. One instance was when Gavin and I pooled our resources, and found we had over twenty dollars, enough to buy two blocks of palm sugar (chindegar). The coolie workers were permitted to have traders sell them food, but we could not buy anything. I decided to try to buy as much as I could, so went with two others into the coolie camp to a hut where business was enacted. I had just bought my sugar, when there were shouts of “Kurra”, and my heart sank, as two guards rushed in, and caught us red-handed. They hauled us back to our camp, where luckily Major Jacobs had heard the noise, and came running. He awoke to the situation immediately, and said, “Go for your lives when I give the word”. As were being threatened by two guards, who were set on shooting us for trying to escape, we were only too keen to agree. Seizing our sugar, and shouting at the top of his voice, Major Jacobs slapped our faces, and quietly said to us “GO”. He took the bundles to the guards, distracting their attention, and we ran for it. An order came from the Nip officer next morning, saying that anyone found outside our camp would be deemed to be escaping and would be shot there and then. Strangely enough, we all got our sugar back, a few days later.

I found a name in my diary, Neil Strike (NX26262); and remembered being unable to eat anything while laid low with malaria, although my mates brought the food, I couldn’t face it and they were worried. So was I. Neil worked with some Dutch Javanese soldiers, and was told certain jungle plants, when cooked, were good for you. They pointed out some of these, and he risked the Nip guards’ wrath by dallying to gather some of the leaves. He cooked them, they looked like spinach, but were something I could eat, and I picked up from then. I had one meal in eleven days, and remember Neil’s kindness gratefully. At one camp, there was a well near our hut. I was very feverish, and woke about two o’clock one morning, to find my waterbottle empty, and a raging thirst in my whole body. This camp was in the cholera area, and we had been warned to drink nothing but boiled or chlorinated water. I grew thirstier by the minute, and thought, “If I am going to die, it won’t be of thirst”, and took a large mug (made from a small billy), and drank about a pint of the well water. No champagne ever tasted more sweet or refreshing. I didn’t die, but I didn’t chance my luck again, with well water.

When we left the Gardens in Singapore for Changi, we had the clothes that we wore and were allowed extra shirt and shorts, blanket, and either ground sheet or cape. I passed my cape in, and thought no more of it two years later, when some clothing was found to be issued to the small group going back to cut wood for the trains, and I was handed a cape with NX72540 stamped on it. Where it had been I’ll never know, but it was in good condition, and most handy.

Among the crowd thrown together, as workers on the line, apart from those already written of, were some great chaps to work with.

Jim Cortis (VX46490), with whom I’d worked in the Bank of Melbourne.

Sid Clerke and Lionel Oldman, who volunteered to go into the cook-house, when our army cooks were unable to cope.

Bert Ford, who went with “F” Force from Bangkok.

Lloyd (Windy) Gale (SX9483) and Teddy , two SXs, who helped keep spirits up.

Pat Jenkin, the strongest of our workers. He challenged a big Nip guard to carry the other end of a pole with him. The Nip couldn’t. I believe Pat after our war, went to Korea.

Pat Lakey (VX62983), a young chap from Maldon, who was a great battler. He had a mate, Tommy Coleman (VX64133) , whom he helped a lot. Tom was a belligerent little chap, who believed in union rules, and took his smoke-oh, whether authorised or not. Unhappily, the man on the other end, usually Pat, would be abused by the guard, unless he also disappeared into the jungle.

Jack Larsen, who was with Bob Whitington, in No. 2 Coy HQ. Jack’s father was in the Royal Navy, landing men at Gallipoli, in WW1. When he saw the Australians being mown down he left the boat, took a dead man’s rifle, and went ashore, and stayed with the Anzacs.

Aub Lawson (NX59271), a cousin of Gavin Shaw, whose house we lived in in Windsor. Aub was a speedway champion, a great Don R, and was evacuated 13.2.1942.

Jim Lynch (SX20270), who disputed one of our officer’s decisions, while carrying on the railway line, by saying, “Fair go, it’s a free country, isn’t it”.

Jack McEvoy (NX65290), a nice quiet, educated chap, whose father was a Scot, and his mother the daughter of the Chinese Ambassador. On ‘F’ Force.

Stan Marchbank (VX64139), from Mildura; has visited Portland a few times.

John (China) Mayberry (VX32008), Don R, came back to his own panel beating business.

Geoff Mills (NX7942), had a cheery grin, worked in C’wealth Bank.

Reg Poole, Jim Stewart and Keith Pope; from Vic Railways. Keith supervised the city kiosks, Jim and Reg were in Tourist Bureau.

Nev Townsend, a quiet chap, good worker, mixed well with everyone.

Tom Morris. I believe he saved a wounded man in Singapore (Bobby Crooks?, under machine gun fire, by crawling up a ditch, grabbing Bobby, and carrying him, still under fir, back to our lines. Un-noticed and unrewarded.

Also, when Boofhead, the Nip cook, would not issue the ration of sugar, but locked it in a box beside his bed, Tom risked his life, by going into Boofhead’s hut while he was asleep, gently taking the key from under his pillow, taking a supply of sugar from the box, locking it; then taking the sugar to the hospital for their use. Tom’s mother had twelve children the eldest daughter was murdered, and when the youngest finally left home, Tom’s mother loved children so much that she adopted another.

Jack McCombe, who was a P.O.W. in Germany, told me he had started a diary, but found he was entering in it, so many ‘same work today’ LIES, that he felt it was a waste of time continuing. Thinking back on the days at Tavoy, each day was much the same, with the exception of Sunday, when at first we had a day off. We had a trader from the village bring food for sale, mostly bananas and pomillos, sometimes eggs, each week. He was given the name “Ali Baba”, and thought it fine, until some one told him of Ali Baba and the Forty thieves. He saw the connection, and lost his happy disposition rather suddenly. We found out after we had left Tavoy that it was noted for its ruby mines. Just prior to our Ruby wedding anniversary, I wrote to the Mayor explaining the reason and asking if I could buy a Tavoy Ruby. I did not receive any reply.

We slipped down the life style scale, working on the railway. Mud seems to have been our main bogey, as well as the attitude of the guards, both Nip and Korean. Moving camp, with as much as you could carry on your back, while two of you carried kitchen utensils on a pole, sloshing through mud for ten kilometres, then finding filthy huts, with an inch or so of mud, and sometimes a stream of water running through the walkway, was not fun. When the dry season came, we had the chance to rid our belongings of bugs and lice, although they were seasonal. It seems that the bugs ate the lice, and later the lice seemed to overwhelm the bugs. We would bounce our bed mats on the ground, bugs would fall out, and the heat of the sun would kill them.

With air raids gradually occurring more often, the Nips began to run the trains at night, and hide them under camouflage in the day, and their camouflage was good. On one occasion a work party was sent up the line to bring back stone ballast. The night was calm, cloudless, and the stars looked beautiful. We shovelled enough ballast into the rail trucks about 1am, and set out on the return trip. On each truck a lookout was posted, and it was quite pleasant lying on the small stones gazing upwards. We saw planes in the distance, but they must have been on their way to bomb Saigon, and we got back without any incident. Had a few hours sleep, then had to spread the ballast.

Going back to Tavoy. When the two runways were completed we were told that a plane would land to test our work. As it approached its touchdown, everyone standing right round the area, was thinking, “Prang you so and so, prang”. And he did! The Nips had no way of moving the plane, so gradually, little pieces of it disappeared. Aluminium plates and spoons and dishes appeared right through the camp.

There were sentry boxes at each corner of the camp, and as absurd as it seems, we, the prisoners, had to do night guard duty, against what I can’t guess, but the opinion was that the Nips were scared of the dark. One night I heard the sound of a tiger, not far away, so was glad to finish my stint.

These are rather trivial items, I know, but I don’t seem able to stop. At one camp, we were guarded by an older man, whom I only saw once. He seemed more sympathetic than the others, and that day no one was bashed. When the lunch-time meal was brought out, he sat near us, and wanted to talk. He was a school teacher in Japan, and because of his age, had been put on guard duty. He went to great pains to give us his version of the war, and said he hated war, and only wanted to get back to his family. He drew diagrams in the dirt, to support his argument, and believed that the U.S.A. had forced them to make the move they did. He said the U.S.A. was putting economic pressure on Japan, so their only means of retaliating was war, and they had to deliver the first blow. At another camp, a very cocky Nip, came across to our smoke-oh group, and said, “Ha, Australia all finish, Darwin bombed, Sydney bombed”. We didn’t know this was true, but thought it some type of propaganda, and someone said, “What about Melbourne?” He replied “Melbourne bom-bom-bom, All finished”. The chap said “Bullshit!”. The Nip said “Hai, Bullshit bom-bom-bom, Finish.” While we were at the first camp, one of the guards was upset at the derision given to his orders in English, so he played his trump card. He got on a box, drew himself up to his full five feet, and said, “You not smart! You think I know f… nothing. I know f… all”, and never found out why everyone nearly died laughing.

The Yanks made sure December 7th was remembered, by flying down the line shooting up everything that looked Japanese. One Australian work party was caught in the middle of a bridge, and had no time to take cover. The officer in charge did some very quick thinking and shouted, “Wave to them. Wave your shirt, hat and your shorts, if you can, but wave like mad.” They all did this, the firing stopped and the plane gave a wiggle of its wings and flew on.

One of the crew of the “Perth” found that elephants are pretty smart, while we were trying to move large clumps of bamboo from the surveyed part of the line. When we were unable to move one, an elephant was called on, and had no trouble in pulling it right out of the way. While we were having our midday meal, the sailor made a ball of rice, and approached the elephant, teasing it by pulling his hand away. He didn’t notice the little steps forward by the elephant, until it grabbed his wrist, and he nearly dirtied his pants. If the owner of the elephant hadn’t made it let go, the sailor probably would have been badly injured. On a work party up river to cut bamboo, we surprised a herd of six elephants, at the river to drink and wash. They disappeared with speed, knocking down quite a lot of bamboo for us.

One of the guards from the Kluang camp took an obvious dislike to me, and soon found a way to show it. While the guard from our camp was away with the truck, obtaining our daily ration, I went down to the barge from our camp, where the woman was doing some washing. I asked her could I use her soap, as I hadn’t had soap for over a year, and I thought I would wash the smell out of my only shirt, when there was a yell from the guard, and he made me go back to the top of the bank where he stood with his bayonet on his rifle. He didn’t hit me but shouted that I was trying to escape, and could be shot for that. He stood me, facing the Thai people from the barges, and put the point of his bayonet in the middle of my back. He was really enjoying his power over me, and wanted me to make a move, so that he could push that bayonet into me. I stood quite still for about twenty minutes, (it seemed like half the day), when I heard the truck come back, and our guard shouting at my captor. Our guard was senior to this one, so I was able to go back to the hut, and then take part in the loading of the barges. The W.O. in charge sent me back on the first barge, and I was very glad to go.

While the floods were raging, many strange things went racing down the river, cattle that had been drowned, timber from bridges that had been knocked down, even parts of huts, and trees. One morning, standing in the bow of the barge, the guard called, “Come, come”, and we saw, as the flood waters surged, a body, appearing and then sinking with the roll of the current. “Thai, Thai”, the guard said, and though it was obviously a Jap, we all agreed most definitely, not wishing to be bashed. Later, we heard that a Jap had fallen, or been pushed off a bridge, further up the river. It made our day.

Strangely enough, the first time I had iced coffee was in Kanburi. Working in the heat at a store, loading the truck, the guard allowed us to rest. The store owner produced two glasses, half filled with ice, and poured some hot coffee on to the ice. It was very much appreciated.

On one hard working day, I was last to get back to the camp, and was thankful to get into the river, and clean myself up. A guard called me, and indicated that I should take two baskets used for carrying meat to the Nip cook-house. They were dripping with blood, and I was as clean as I could be under the circumstances. I said, “Not these bloody baskets”; and received a bashing from the Nip for calling him a bloody bastard! No doubt, a case of a little knowledge being a dangerous thing, for me. That job was the best I had, getting us away from the camp, and giving us some sort of freedom, for part of the day.

The officers were taken from our camp to a special camp at Ratburi, and I did not see Gavin again until we met in Bangkok. We felt that plans were being made for us to go on more work parties. Air raids to nearby areas became more frequent; Kanburi railway yards and the Wampo Bridge being the main targets. On one occasion I think it was 7th December, American planes followed the railway line, bombing bridges and damaging any object that could help the Japanese war effort, such as sidings and buildings, even culverts. Our steel bridge was attacked, but because of its open structure, not a great deal or damage was sustained. However some bombs landed in the mud and failed to explode, and we were given the job of removing them and disposing of them further upstream, in the river. After this the Jap engineers decided to build a second wooden bridge, slightly downstream from the steel bridge.

One of the less popular means of using us, was to take work parties to the corners of the camp where the ack-ack guns were placed. We cut green branches from trees to put in large bamboo containers with water, rather like vases of flowers, and keep the area clean. On one occasion, the British work party had put the camouflage around, and were working in the ammunition shed, when the alarm was sounded for an air raid. The Nips immediately slammed the door of the shed, and locked it, giving the poor old Poms a very nasty half hour.

We heard the next party out was a work party to Japan, and only white people were to go. I think this was to aid to our humiliation, as the papers that we managed to see, still spoke of the Greater South East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere, aimed at bringing the Thais and Burmese into Japanese dominance. On the first parade, the fittest men were selected. I was shivering with malaria at the time, so missed that trip. I was well again when the next work party was to be sent, and stood on the parade ground with all my kit. The guard doing the counting got as far as the man next to me, and said “Finish”. That was the party on the ship that was torpedoed by the Americans.

The Nips then decided to close the camp, and move the remaining men to Kluang, a short distance away on another branch of the river. It had a huge cemetery, mostly British, and I was given a job placing crosses on graves. There was a permanent burial party, as it was a hospital camp, and a team made crosses and located graves. There was an unfortunate error made when a cross was placed on a Jewish Soldier’s grave. It was soon replaced with a star, and a lesson was learned. At the far end of the cemetery was a huge mango tree, but I was not in the camp long enough to benefit. I took over a garden plot with peanut plants and tomatoes growing, but was moved out before they ripened. No one wanted to be sent to work on the Wampo Bridge, as it was constantly bombed. It seemed that as soon as the bridge was repaired, it was bombed again. However, I could not escape, after an American bombing had done heavy damage everywhere. From our camps, both Tamarkan and Kluang, we could hear the attacks on the bridge. We were not sent with the engineers party to repair the bridge, but were a carrying party, which was kept out of sight in the daytime, and unloaded railway tracks at night, loading this onto barges, which took it across the river, where another party, whom we never saw, loaded it on to a second train, which took its load up to the front line. We carried everything, two men on a pole, Tom Beenie working mostly with me. I was on the back position, so that I could get my hand into the baskets without being seen. We were able to add to our food supplies by this means. We lived in tents on a sandy spit, with guards, a Nip cook, and lots of slit trenches. The stupid cook would panic when air raid alarm was given, and would make anyone standing near throw water on his fire. This sent a column of smoke into the air letting any observer know that a camp was there. We had two air raids while we were there, and the accuracy of the British bombers was amazing. One of our engineers, who was caught in the middle of the bridge, and was able to squeeze into a cave in the wall of the cutting, said that in five bombs dropped, four were direct hits, and one a near miss. It was fascinating to watch the planes peal off, and make a run towards the bridge, trying to calculate as the bomb bays opened, if the bomb could hit us. One of our party, declared he would stay in his bunk, while we were in the slit trenches. The ground would reverberate each time a bomb exploded, but he stayed on until one day, the blunt end of the bomb, a solid piece of steel, about two feet in diameter, whistled through the air, and his tent, and landed a few feet from him. After that he was happy to join us.