|

|

![]()

| Escape from Singapore --- 1942 |

| By Lieut.John Prior Purvis R.A. |

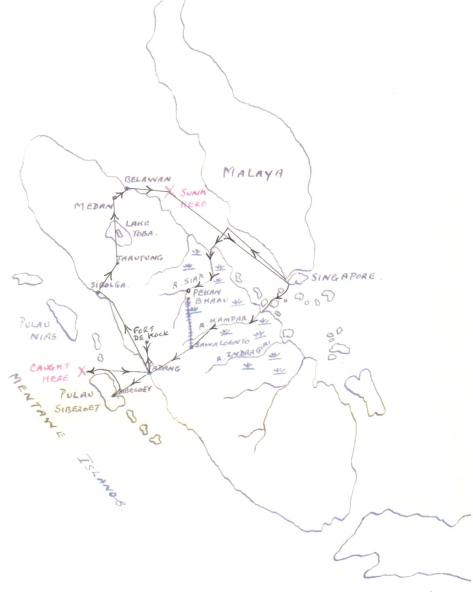

Escape from Singapore - Across Sumatra to Padang - Escape from Padang, headed for India - Captured and became POW - To Medan and NW of Sumatra - Ship torpedoed when moved to Singapore - Finally on the Sumatra Railway

Part One---Escape

Chapter 1---By Sea

This is the story of the escape from Singapore Island of part of 22nd Battery 3rd H.A.A. Regiment R.A., in the early morning of Monday after the surrender at 8.0pm on Sunday evening, 15th February 1942. The writer was a Lieutenant in command of No. 4 Section which had been withdrawn on Friday night from Pasir Panjang Road after destroying their guns and electrical equipment. The order to destroy this equipment was given about midnight on Friday and the Section was instructed to march to Kalang Aerodrome and to await further orders. When we got there we were billeted in a small house opposite the Aerodrome and this was also the Battery Headquarters. On the Saturday, when it became obvious that Singapore was about to collapse, the Battery Commander, Major G.A.Rowley-Conwy, called the Battery Captain - R.W. (Peter) Morley - and me to his room and said "It seems ridiculous to hand ourselves over to the Japanese. What do you think of the scheme of taking one of the big junks lying in the harbour and putting the Battery on board and making our way across to Sumatra where we shall undoubtedly find other members of the British Army and Dutch Allies with whom we can carry on the good work?" I said I thought it was a good idea although it was quite a mad thing to do as we should be a sitting target for the Japanese aircraft. Our own aeroplanes had left the island for good more than a week before and the Japanese were able to fly unmolested, except for desultory ack ack fire, when and where they pleased. We discussed this at some length and my Battery Commander's enthusiasm led me finally to agree that it was the obvious thing to do and from that time onwards we began to think in terms of accumulating tin rations which could be easily transported to the junk when the time came. We also reconnoitred Thornycroft's Yard in Tanjong Rhu to see if there were any boats which we could use to take the Battery out to the junk. We found two motor boat hulls without engines.

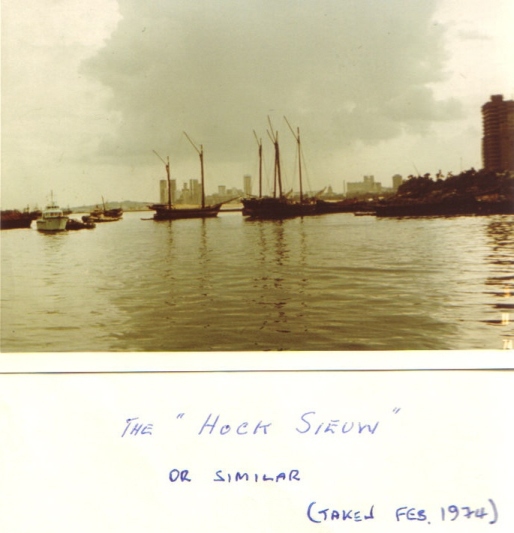

We had more or less decided which junk we were going to have. It was a large cargo carrying Indian Tongkang two masted ship called the 'Hock Sieuw', with braille rig, loose footed mainsail, mizzen and two headsails. Under sail these boats are very beautiful and remind one of ancient days with their bowsprit pointing skywards and high stern. Sunday evening came at last while we were supposed to be defending Kalang Aerodrome with a few rifles, bayonets and bandoliers of ammunition. Thank God the Japanese did not arrive or I am sure they would have made very short work of us. Later that evening, Peter Morley came tearing down the road on a motor-cycle and told the Major and me that General Sir A.E.Percival had driven out in a motor-car with a white flag to meet the Japanese Commander and surrendered the Island. This was sufficient for us and we commenced to work our way down to Thornycroft's Yard.

We quickly loaded up two large unfinished motor-launches with all the tins of food we could lay our hands on and commenced to ferry men and food to the Tongkang we had earmarked. This job took us nearly all night and was much more hazardous than it had appeared or we expected. While we were paddling our over-crowded boats out the Tongkang we found there was a terrific tide and it was quite a job to reach the boat. Every man was armed with a rifle and as much ammunition as he could find and we also loaded several boxes of Mills bombs and two Lewis machine guns. We intended at any event to give as good an account of ourselves as we possibly could if we should be unfortunate enough to run into any Japanese, and we clambered aboard the junk, armed to the teeth.

One snag occurred here. The Major told me he had managed to find a Naval Officer who was going to give him some charts of the harbour, unfortunately the Naval Officer did not turn up - neither did the plans. This meant that we had to be extremely careful gong out of the harbour because of a minefield to port and rocks to starboard which left only a narrow channel though which to navigate. There was plenty of evidence of the minefield with many masts of boats which had run onto it sticking out of the water. While we were boarding the ship a party of 10 Australians arrived and demanded that we took them with us, which we did. At about 3.0 a.m. on Monday morning we were loaded up with 169 volunteers, including 4 Officers and the Battery Commander, Battery Captain, Lt Lewis Davies and myself.

I am not going to attempt to describe the picture of Singapore in the last hours of its agony except to say the whole place appeared to be in flames. The oil storage tanks had been blown up and oil was running in flames down many of the monsoon drains and out into the sea and there were huge fires burning everywhere so that the entire harbour was lit up. Sporadic gunfire was going on, or it may have been explosions of ammunition. As we weighed anchor, if I had not had so much else to think about I think I would have wept for Singapore, the so-called impregnable fortress.

Now, however, there was much to do to think of sentimental things and we weighed anchor and set off on the beginning of a very long and exciting journey to Sumatra and as far as I was concerned it was a journey into the unknown. For navigational aids we had only one page of a school atlas with Malaya and Sumatra shown on it. There was no compass in the boat and after getting out of the harbour the idea was to point to the west and hope for the best. Fortunately there was a barrel of water on board the boat and without it we should have been in difficulties because we were not able to take any with us; but even so the water ration was going to be very small.

We crept along what we believed to be the channel in between the minefield to Port and the rocks to Starboard lining the southernmost tip of Singapore Island and Blakangmati Island and the St John's Island and Little Peak Island. There was a slight breeze which was just sufficient to get the boat underway.

The night would have been dark had it not been for the fires in Singapore and we crept along hoping to be clear before dawn. This was not to be, however, as just about when dawn was coming up we ran onto a pile of rocks off St John's Island and with the tide running very fast it was not long before we were high and dry. I remember the Major shouting to the helmsman to "whip her round" but, of course, you cannot whip round a 150 ton junk and it was too late. There we were stuck on this mound of rocks with Japanese aircraft flying over-head and expecting any minute we should be bombed out of existence but fortunately none of them took any notice of us. After a bit the tide ran out still further and it was possible to walk to the Island and at this point the Major called me and said "What do you think John? Do you think it will be possible to get off these rocks?" and I replied "I very much doubt it. It looks as if we are well and truly wedged". He then said he thought he would walk to the Island across the sand and see if he could obtain assistance or other boats in which to continue our escape. He went off with Davies, the Quartermaster, and Tiffy and about 25 others but none of them returned and that night we found ourselves still on the rocks and numbering about 140 strong.

Peter Morley and I, being left now on our own, discussed the situation and wondered what was best to do. We both agreed that it would be wrong to leave all these men and therefore decided to stick with them and if we were captured it was just too bad. We did, however, decide to go and find some Malays who were living on the Island and see if they could suggest any means of getting off the rocks. Peter came back and said that the Malays were quite cheerful about getting us off and didn't seem to think there was much difficulty. This was the most joyful news we had had, and at high tide we expected them but alas they did not come. We went to find out why and in their charming, smiling way they said that they would be along at the next high tide. This meant that we were to be exposed to the dangers of the Japanese for two days and two nights but our luck held. With the next high tide along came a whole lot of Malay canoes and they pulled this way and that and to our great surprise we found ourselves afloat once more. With cheers and shouts and salaams we set off again and managed to sail clear of the area which we knew was mined.

Unfortunately none of us had the slightest idea where we were nor could we tell which of the various pieces of land we saw from time to time was Sumatra so we had to make one or two stops. This, with an untrained crew, was extremely hazardous although we were fortunate to have the services of a man called Farwell, who had served in the schooner Madelaine, and also an ex Thames bargeman called Foden. These two, and I, were the mainstay of the crew. I had no idea that there were so many small islands between Singapore and Sumatra, because they were not marked on our school atlas.

When it rained, as it did several times, we managed to collect water on the sails and replenish our supplies although even then the ration was only a 50 Goldflake tin per man per day and this when sailing on the Equator is not much. Rations consisted of two very small meals a day of M & V heated up in the galley (which was a job worthy of the "specialist") stuck up on the aft part of the ship. We managed to purchase a little fish off one of the islands.

We continued sailing for another day or two when we ran aground on a sandbank while we were passing between what we thought were two islands. Most of the men jumped over to have a bathe and while I was standing on the poop with Farwell he turned to me and said "Look at that man in the water having a wash, he is covered with lather". I looked and sure enough he was. "Skipper", I said "we must be in fresh water, which means we must be in a river, which means we must be in Sumatra". So at this point we decided to wait till we got off the sandbank and carry on up whichever river we had entered and see what happened. In due course the tide floated us off the bank and with a gentle wind behind us we went upstream. We had not gone very far however when we went onto another sandbank and this time I decided to take a small boat with a part of eight and go and explore around the next reaches. We rowed some distance up the river until we came to a large sandbank where we pulled the boat up and decided to have a look around. On this bank were spores of large animals and flocks of large heron and there was a constant chatter of animals in the jungle bordering the river. We had a few shots at the heron and at a pig which rather foolishly ran onto the sandbank but we were not successful in obtaining any food that way.

When we left the boat on the bank I detailed a man to look after it and move it down as the tide went out but unfortunately on our return I found that he had gone off on his own and the boat was high and dry at least a quarter of a mile from the water's edge. When we came to lift the boat we found this almost impossible to do and it required a great effort to get it back to the water. The man who had left the boat returned just in time to help push it back in the water. We rowed our way back to the junk feeling rather disconsolate.

On arrival I had a conference with Peter Morley and Skipper Farwell to decide what we were going to do. Up to now we had only seen one human being in a canoe and he had scuttled away as fast as he could so there was no one we could speak to and find out where we were. We decided then and there to about turn and get out of this river we were in, where there appeared to be no habitation, and go south down the coast of Sumatra until we came to some village or small town where we could find out what was going on. So early next morning we set sail again and I must admit it was a most glorious sail taking the junk out of this large river, against a good stiff breeze with all sails set. When we were near the entrance we saw two Malays in canoes and we sailed the boat towards one of them. He appeared to be most interested and, as we passed, clutched a line and came aboard. One or two of us speak a few words of Malay and we questioned him as to where we were and he said that we were in the river Kampar and he would be pleased to take us to his house and make arrangements for us to go on up the river with some Chinese that he knew.

It really looked now as if we might be getting somewhere so we about turned again and with him on board sailed the boat back past the place where we had previously gone aground. When we had gone about half a mile further on he told us to drop anchor and on looking into the jungle we could see two tiny, rather miserable, dwelling houses. This was where he lived, apparently alone. This Malay was extremely kind to us and supplied us with rice and vegetables and coconuts and after staying there for two days he obtained two sampans, each manned by a Malay boy and it was in these that we were to spend our next four days and nights on our way up the river Kampar. These sampans were owned by a Chinaman. As we had no money to pay him we gave him the 150 ton junk in exchange, not that it was ours to give, but he seemed very happy when I handed him a little note saying that we had requisitioned the junk and gave it to him in exchange for further transportation. Off we went again for a very cramped but, on reflection, very pleasant journey during which time we fed almost exclusively on coconuts. It was during this trip that we realised why the river was not more inhabited which was due to the fact that the river has a tidal bore that occurs every so often and while we were in the sampans the Malay excitedly called our attention to the bore as it slowly came up the river. Each night we pulled into the bank and slept in the jungle - subject that is to the attacks of ants, spiders, mosquitos etc. Eventually, as the river got narrower, we came to a place called Tebk Ayer where the Chinaman had a small shop. This was a charming little typical Malay village, with its houses on stilts, many of them over the water and here we were received kindly and housed for the night. In exchange for this accommodation and excellent meal of Nasi Goreng (fried rice with fish, etc), we gave the Chinaman a brand new Evinrude twin outboard engine that we had taken from Thornycroft's Yard in Singapore and kept in the hopes that we would be able to make it start but we were never successful. In all the Chinaman did very well in obtaining a junk and a new outboard engine. This was the end of our seagoing trip and from here onwards we had to march through jungle and swamps, some 75 miles, before we reached civilisation where we hoped to find some motor transport. At this point we were still optimistic of joining up with some organized Army force as up to now we had not seen or heard anything of the Japanese.

Chapter 2---By Land

After this very welcome rest in the Chinaman's shop and hutments at the back, we awoke and set forth on what was to be a very exciting march through the jungle. We acquired little in the way of provisions from the shop but we were successful in obtaining a guide who promised to take us to the next village. For the next few days there were, of course, no roads and we had to walk single file along the twisting jungle paths and wade through tributaries of the big rivers which run from west to east of Sumatra. As the central portion of the east coast is mostly swamp, going was extremely hard and on one occasion we had to cross a very deep swamp by means of walking along tree trunks which had been felled in a rough line through the middle of it. The art of walking along these tree trunks is not as easy as it sounds and there were quite a few in the party who found it very difficult to balance with the result that frequently men slipped off these trunks where they went up to their necks in water. I did myself on one occasion but luckily I was lodged on a branch and was able to keep my rifle and ammunition dry. The largest of these swamps we had to cross was reached about 6.30pm in the evening which is just before dusk and knowing nothing of the difficulties ahead we gaily commenced to cross with the guide in the lead. The difficulties I have mentioned were soon apparent and after about 45 minutes it became dark - there is practically no twilight on the Equator - and from this time onwards we had to walk in inky blackness, unable to see one's hand in front of one's face and at the same time balance on these logs, while the direction of each trunk was slightly different to the previous one. It was one of the most difficult passages I have ever made. We were obliged literally to inch our way along sideways holding hands and I suppose eventually we must have pretty well stretched across the swamp. As I have said, we entered at 6.30pm and the last man came out the other side at 3am in the morning and, although I cannot be certain, I don't suppose we went more than a couple of miles.

It was here that we had our first bit of military indiscipline. One of my men was ill and was being helped along the logs by his friend, a Bdr. Carr. During the night he fell off and naturally there was a hold-up while his mates tried to haul him up. Immediately behind came two officers - they had boarded the junk with us but were strangers to me. One of them shouted at Carr to get on and when Carr pointed out what had happened, the officer yelled at him to use the man as a stepping stone and get on. Carr then drew his revolver and told the officer that if he took one step forward he would shoot him. The officer waited and on arrival at the other side tried to place the Bdr. under arrest, and came to report the incident to Peter Morley and myself. I'm afraid Peter and I decided to take no action - our sympathies were with Carr and the officer was a nasty bit of work anyway. He threatened to take the matter up later on - what a hope he had!

On the other side of this swamp was a most charming village and on our arrival the headman and a number of other dignitaries turned out to greet us. Our guide explained who we were and that we wanted accommodation and they willingly did all they could to help. Our officers were given a hut on stilts and we went in only too thankful to take off our heavy kit and lie down for the remainder of the night.

It was quite cold and to my surprise the natives had lit a small fire in the fireplace despite the fact that the hut was of the usual construction of bamboo and palm leaves. We soon went off to sleep. I awoke early and as it was rather cold I decided to bank up the fire but unfortunately I overdid it and as the flames leapt up they caught the sides of the fireplace alight and within a matter of seconds the entire house, measuring about 12' square, was ablaze. The alarm awoke the other officers and we hurled out of the open doorway as much in the way of kit as we could without being enveloped ourselves in the flames. It was extremely bad luck that most of our stuff was lost and poor Peter Morley had the misfortune to lose his boots, which meant that he had to complete the journey of several days duration with no boots. The alarm soon spread through the village and the natives came rushing from all quarters shouting "Padi Padi" which I soon discovered meant that they were fearful for their sowing rice which was stored under the house. The loss of this seed would obviously be a great tragedy to the village. We formed a chain of men between the house and the well which was some 100 yards away and we were, thank heavens, able to save the Padi, but not, of course, the house. It is extraordinary how good natured Malays are because when it was all over they gave us what food they could and did not seem in the least bit worried about the house as we had managed to save the rice. We gave the headman $10 (25/-) and he was perfectly satisfied and obviously thought we had behaved in a proper manner.

From here we recommenced our journey having obtained a new guide and straggled our way through the heat of the day to the next village where we rested again, luckily without any unfortunate incidents. We were finding the greatest difficulty in obtaining food as apparently another party had come along more or less the same route and had removed the spare chickens before we got there. For the most time we had one large meal in the evening which consisted of a large container of rice with a few vegetables and possibly one chicken to give it a little flavour but this was not much amongst 140 men.

On the third day we very nearly had a major tragedy in that we were walking up a small river or stream following our guide and at the rear something happened to cause the last 10 men to pause and the rest of the party went out of sight. Unluckily for them the stream forked a little further on and when they reached it they took the wrong fork. This could easily have proved disastrous as the jungle in this part is not particularly inviting and villages are few and far between. Fortunately they met a native who conducted them to where he guessed we would be walking, which was to the end of the road the Dutch had been preparing for their new oil wells but which had ceased because of the war.

By the end of the fourth day's march I was getting very tired indeed and I remember being rather at the rear of the party and when we arrived at the village in which we were going to sleep there was Peter Morley and some of his chaps with great bundles of green sugar cane. Each of us was handed one of these and I can honestly say I have never enjoyed sugar as much as I did that moment. We bit into these lovely canes and sucked down the raw sweet juice which greatly revived us.

We stayed the night here and set off again in the morning with a new guide who assured us that there was a road with motorcars not very far ahead. During the day it was unusually hot and most of us were visibly flagging but fortunately about the middle of the day - I cannot say lunchtime because there was no lunch - we came across the beginning of this new road as we marched from a clearing in the jungle. Needless to say there were no motorcars but nevertheless the going, we hoped, would be easier from now on. We had not realised, however, that once out of the jungle we were to march under the merciless heat of the mid-day sun. After plodding along this road for a couple of hours we came across a fairly large stream which spilt over the road and had formed a pond on the other side and as it ran off the road it made a very small waterfall. This was irresistible and we all stripped and jumped in and splashed about in this glorious cold water. This bathe bucked us all up so much that we went on quite a bit faster until, to our enormous joy, we saw a lorry. This was the first glimpse of European organisation that we had seen for many days and soon we had arranged with the driver to fetch one more lorry and take us to his rubber plantation. There we met two Swiss planters who made their small guest house our quarters and told us to help ourselves to any of the tinned food etc. which they had stored there. These planters were extremely kind and made us very welcome. They gave us up to date news of the war which, of course, was still very bad and said that we had better go to the local town where there was a Dutch controller who would fix us up with everything and arrange transport. Meanwhile they would send us there in the estate lorries during the morning.

When we reached the market town we immediately went to see the Controller who was a most unpleasant man. He agreed to help us but thought we were running away. He appeared to have no idea whether there were any Dutch army units in the vicinity and did not know where the Japanese were although they had just attacked Sumatra. His anger, I suppose, can be explained by the fact that the Dutch have always hidden behind the British in Singapore and when the latter fell it left them exposed and required them to do their own fighting. This they were not prepared to do. The Controller explained that he would send us by bus to Sawaloento - a railhead in the mountains - and from there we could get a train to Padang on the west coast, where he said many others had already congregated, and from whence the Royal Navy was taking troops off. This was news to us. I remember sitting with Peter Morley and feeling very gloomy about our chances of being taken off because we had been so long over our journey - about nine days so far. The Japanese were obviously going to overrun the island without any difficulty and we looked like being too late. Peter, who was ever an optimist, told me not to be an ass, but I'm afraid I was to be proved right in the end.

The Controller eventually produced the most rickety bus which was to drive us through the mountains to the railhead. This was the most hair-raising drive round mountain passes at incredible speeds, accompanied by almost non-stop horn blowing by, what I thought, was a half-crazed driver. We arrived, however, in one piece although, thinking it over, I do not know how we did it. At the railhead we were put into a train that took us to Padang, a charming, small town and port on the west coast of Sumatra, just about on the Equator, where we were met by British Naval officers, who, I must admit, were a great joy to see. It was rather annoying though to be told to hand over our rifles and ammunition which we had so carefully carried on our long march. The officers, however, were allowed to keep their revolvers but as I only had four rounds of ammunition for my 4.5 I did not suppose it would prove of much value.

Then followed the most extraordinary week for me in which I was billeted in the Hotel Centraal, which is the biggest and best hotel in Padang. I had a room to myself and a Javanese boy to look after me and I need hardly add that I really enjoyed myself. We took our food in the hotel and everything for those few days was marvellous. Unfortunately about the middle of the week it became apparent that the Royal Navy did not intend to pay any more calls to Padang and several thousand officers and other ranks of the Navy and Army who were in Padang were to be left to their fate. Actually hundreds had been rescued but they were the ones who got there early. Ironically they may have been some who left Singapore before the end. It wasn't until now that I realised there was an escape route laid on for V.I.P's and certain others. Unluckily for us we entered the wrong river. The official route was up the River Indragiri and we went up the Kampar. While we were at Padang there were constant rumours of the arrival of destroyers to take us away the following night but obviously it was too dangerous and nothing ever came of it. I again met my Battery Commander who left us on the rocks off Singapore. He was in great form and had just got himself into a small party of officers considered worth saving who were to be given a properly provisioned sailing boat to sail to India. His party made the trip in six weeks and all arrived safe and sound. I was to try later but without the same advantages and without success.

On the sixth night of my luxurious living I was suddenly ordered to leave the hotel as the Japanese were expected to arrive in the town the following morning and I was put into a warehouse with scores of other officers and men. There was no resistance by the Dutch as Padang had been declared an open town and surrendered long before the Japanese came anywhere near it.

Chapter 3---By sea again & capture

During the night I was lying on the floor of the warehouse next to another officer, a Captain Apthorpe, and a soldier came over and began whispering to him. Not unnaturally, I listened and to my great joy I heard him telling Apthorpe that a number of soldiers were attempting to take a native prahu and escape but, were experiencing difficulties. I pricked my ears up at this as I had been lying there wondering what on earth I was going to do when the Japanese arrived in a few hours time. The idea of this boat awoke me to the need of taking some positive action. I discussed the matter quickly with Peter Morley who decided not to try and escape because he felt it was his duty to stay with the troops we had brought over from Malaya but he agreed that it would be right for me to have a go. Captain Apthorpe and I and the soldier then crept down to the river where Padang has a harbour with an entrance to the Indian Ocean. There we saw the boat of about 40 tons of fore and aft rig, the mainsail having a standing gaff. It was decked in fore and aft having a bamboo roof over the cargo hold and a small cabin aft. We walked aboard and there met a gang of ruffians whom I would describe as some of the lowest types of the army, a mixture of English and Australians. When we two officers went on board the soldiers who were taking the boat immediately objected and tried to chuck us off and, in fact, we found ourselves back on the dockside again. They said they weren't going to have any "effing" officers on their boat! However, fortunately for us, none of the soldiers appeared to know how to handle a sailing craft and this boat had no engine. This was a bit of luck for me because I was able to say to the biggest thug, who appeared to be taking charge that he would not get far if he did not have someone on board who knew how to handle it. To this he agreed and by now two more officers had turned up and all of us were graciously permitted to come aboard.

We had difficulty in obtaining water but we found an old drum and filled that and in the dead of night, about 3.0am, with no wind whatever, we poled our way out of the river. It was a dark night and very difficult to see exactly where we were going and I knew that at the mouth of the river there was a large sandbank and all I could do was pray that we should get round it successfully. Having negotiated that we had the rollers from the Indian Ocean to cope with too but when you are trying to escape from what we thought was a fate worse than death you make light of almost any difficulties. We had one great stroke of luck while we were poling our way out of the river and which went to prove we were only just in time because round the end of the docks came three Japanese armoured cars. They shone their headlamps on us and I expected any moment they would open fire but I can only think they must have thought we were natives going about our ordinary business because they took no action and drove a little further up the docks. This was a lucky omen and filled us all with great encouragement. We got the sails up and continued poling our way out through the rollers until the depth was too great and then we picked up a little breeze from the south and proceeded due west. At this stage I regret to say I had no plans as the only thing to do was to get away from the land and then think what was best to be done.

We had in mind sailing the boat to India or possibly Australia. The boat had a dry card compass but, of course, we did not know whether it was accurate. We were fortunate in having a school map of the Dutch East Indies which was some help towards pointing the boat in the right direction! I am sorry to say nobody on board knew anything about navigation. The light southerly wind was hardly sufficient to give us headway but we slowly drew away from the mainland.

As I have said, the crew were the dregs of the Army and greatly resented being given any orders. I explained to them that to sail a boat properly the man in charge must give orders - it was not a question of officers buggering men about - and it was essential that those orders be carried out quickly and efficiently. Finally, I had to tell them that I would refuse to sail the boat unless they agreed to do what I wanted, which, after all, was only for the good of all concerned. After a lot of muttering they saw my point and an uneasy truce was made, but I was always expecting trouble and, of course, eventually it came with disastrous consequences.

Lying ahead was a tiny island - just the peak of a mountain - and as it lay on our path we decided to sail quite close to it. To do this was fortunate because as we approached we saw men on it waving to us. We drew as near as we dared and dropped an anchor. Six men clambered into a canoe and paddled out to our boat, which by the way was called Bintang Dua (Star 11). We received the six men on board and they asked if we would take then with us to which I readily agreed. We were lucky to meet them because one of them, Sgt Straccino, was a first class engineer with knowledge of sailing and a little navigation. Two of the others were merchant seamen and the remaining three were just bods. Needless to say there was a conference amongst the crew of Bintang Dua and finally their leader, an Australian, came over and said "Youse Skipper" so I said I would be pleased to take them and now there were four of us on board who knew something about sailing. The total ship's company numbered 26.

From this island we continued very slowly on our way and when the evening came we had made but a few miles. During the night a tremendous storm blew up which ripped the mainsail from gaff to boom and blew us almost back to Padang harbour. With the dawn, however, it ceased and a really pleasant wind took its place. This enabled us to about turn again and head for the island of Siberoet which lay about 90 miles to westward. We had only half a mainsail at this stage but in actual fact the boat went better and certainly carried far less weather helm. All these vessels are built to carry cargoes of rice, wood or coconuts and none have much in the way of a keel. We were fortunate, however, in having a wind on the port quarter and we sailed all day and all night and in the morning there we saw land which we hoped was the island of Siberoet. There was one town marked on the map but we could not tell which part of the island we were looking at and so we decided to enter what looked like the mouth of some river but on getting there we found it was a mangrove swamp and led nowhere. In order to explore our way through this Sgt Straccino went up the mast where he was able to see the depth of the water ahead and the outlines of the mud banks while I steered the boat to his instructions.

We came out of the swamp and sailed on for a mile or two when we saw a small village, so we decided to drop anchor and go ashore and try and find out exactly where we were. We sailed the boat as near to land as we dared and jumped overboard and swam the rest. We walked up to the village and with some difficulty found that the town of Siberoet, which was marked on the map, was in fact a few miles to the south. With that information we departed and swam back to the boat. With a light breeze we continued on until we came to the entrance of what looked like a small river and to our joy we saw a large village about a quarter of a mile up the creek. We carefully worked our way round the mud banks and finally tied up against a wooden jetty which was obviously used for unloading the cargo ships of such imports as the island needed. On jumping ashore we were met by the headman who had come out to see who we were and what we were doing. He was obviously very nervous and not particularly pleased to see us although, to his credit, he did all he could to help us. It must be remembered that these natives knew they might get into trouble with the Japanese if they helped escaping troops and, not unnaturally, they would rather we had gone elsewhere. We spent several days in this village and bought every tin of food which the islanders were prepared to sell but they were not inclined to sell much because they knew perfectly well there might be a shortage of food on their island later on. For us, however, it was imperative to get sufficient supplies to last for at least 8 weeks as we reckoned it might easily take that to sail across the Indian Ocean to India. We experienced our greatest difficulties in supplying the ship with water. There were no water cans on board nor could the natives produce any and at one time it looked as though the trip was going to be impossible owing to the lack of water. However, the Controller when he heard of our problem came along with an excellent solution. He ordered the natives to go into the jungle and cut 8' lengths of large bamboo 6"-8" in diameter and bring them to the boat. When they arrived with about four dozen huge bamboos he showed us that if you break all the joints inside the bamboo except the last one you have an excellent water container which would hold many gallons. With this marvellous idea it was possible we thought to equip the vessel with sufficient water to carry us, at any rate, up to the islands further north where we could replenish our supplies before attempting the final crossing. We filled up the bamboos with water and laid them crisscross on the roof and lashed them down with rattan. During this time the natives repaired our mainsail and I decided to put several sacks of ballast in the stern of our boat which had carried so much weather helm on the trip over and I believe that frequently the rudder, which was a skinny little thing, was out of the water. The natives were horrified when they saw what we were up to and gesticulated, but rightly or wrongly we went on with what we were doing.

While all this was going on a large canoe-type boat with out-riggers sailed into the harbour with a party who were escaping in the same way as us. They suggested that we all go on our boat because it was larger and more seaworthy but unfortunately it was considered by the crew of our boat that we could not carry supplies for a further eight men and we had to tell them that we could not take them. I afterwards heard that they had a magnificent struggle and actually sailed to Burma where they were captured by the Japanese and several of them died.

We had a very amusing time getting to know the natives, most of whom lived in the village and were Chinese and Malays and quite civilised people but in the interior there lived an extremely primitive race who wore only a loin cloth and carried bows and a quiver full of arrows. These men were tattooed from head to foot with vertical lines and occasional streaks across their bodies. They were small but quite well-developed with long black and rather itchy looking hair. They brought in huge bunches of bananas and live pigs and before we parted we put three live pigs on board, twelve chickens and many large stems of bananas. Later on we were to come across these primitive natives again and to find out that they were, in fact, quite useless when asked to lend a hand. Meanwhile we had many long discussions as to whether we should sail to India or Australia via Java. On our page of school atlas either journey looked perfectly simple! Eventually the majority decided on India - so India it was to be.

At last everything on the boat was shipshape and we went along to say good-bye to the Eurasian Controller of the island. He shook hands with us and wished us well and was obviously very glad to see us go. With that we sailed out of the creek and headed northward with the idea of making our first call at Pulau Nias. The wind, however, was from the northward and we sailed for two days making long tacks but unfortunately very little progress owing to the light winds and the fact that our boat made so much leeway, being high out of the water. I think the ballast I put in the boat helped the steering a bit but truly the boat should have been loaded with cargo if it was to go to windward at all. During the second day we killed one of our live pigs and had a magnificent meal. We also had great fun with the chickens which lived in the hold with members of the crew. The pigs, poor blighters, we had lashed down on the small area of foredeck. Although progress was slow we were, in fact, making headway until the third day when we came to grief. I was lying resting in the small cabin aft, which incidentally was absolutely black with cockroaches, and if I had not been so utterly worn out I do not think I could have laid down in it. At the helm was Sgt Straccino and the boat was actually sailing along on the starboard tack towards the island of Siberoet. I was woken up by a cry from the helmsman telling the foredeck hands to get a jerk on and get their jib back. I lay there realising that we were going on to the port tack to stand off the island again when I heard another shout that if they did not look out we should be on a reef. At this I leapt up and rushed up to the deck where I beheld waves breaking across a large coral reef towards which we were heading and our ruffian crew were apparently sullenly refusing to assist in the manoeuvre of going about. Without waiting to say anything I rushed up and attempted to back the foresail on my own with Straccino putting his helm hard over but unfortunately it was too late and the boat drove on to the coral reef and there stuck fast with a grinding crash.

This reef was possibly three to four miles off the shore and on inspection I found there were two holes in the hull - one about on the waterline and one just below and the rudder had been severely damaged. We got to work to plug the holes as best we could to keep the water out and then it seemed to me it might be possible, if the tide was rising, to push the boat off; so I ordered everyone to jump overboard and stand on the coral reef in the hope that we might be able to rock the boat clear.

It was extraordinary, however, how many non-swimmers there appeared to be on board because only six of us jumped over and it was quite impossible for us few to do what I intended. The others just refused to help. As this failed and the boat was leaking considerably I ordered all non-swimmers to get into the large dinghy we were towing and to go ashore in the charge of Dick Tranter, an Australian Officer, while I would stay on the Bintang Dua with a small party of good swimmers who could keep bailing until such time as I hoped the tide would rise and float us clear or some natives arrive to lend a hand. Once again the non-swimmers came to the fore and all piled into the dinghy leaving six of us on board. We spent all night working in shifts and managed to keep the water down to reasonable proportions and in the morning a canoe arrived with several natives in it who had seen our plight and with their help we re-floated our boat and managed to get it across the stretch of water into a small creek between the reef and the island. We hoped to effect repairs which would enable us to continue our journey. Our non-swimmers rejoined us and we set to work to repair the rudder and the two holes. Once again Sgt Straccino was a great tower of strength as he was an engineer. Repairs to the rudder were done by diving and holding our breath but this work under water naturally took us quite a long time. While we were doing these repairs our old Mentawai native friends arrived from the jungle and with excited exclamations were apparently going to lend us a hand, but in actual fact all they did was to sit on the deck watching us and scratching them selves. One of them was most amusing when he heard that my name was John because he had been christened Johnathan by a Missionary a short time beforehand and he jumped up and down with a broad grin, scratching himself all the harder.

'These Mentawai natives who live in the interior of Siberoet are animists, who believe everything has a spirit. Unfortunately for them nearly all the spirits seem to be, if not hostile, at least on the look out to do them down if possible, with the result that if you ask one what his name is he is most unlikely to tell you his correct name in case the spirits are watching and will do something to him when they learn who he is. In the same way if you ask him where he is going he will tell you that he is going in the opposite direction because a spirit is sure to be listening and will be waiting for him when he reaches his destination. This animistic belief causes him untold troubles and in fact a man and a woman do not get married until their children have had children. This is because if the spirits saw them getting married they would undoubtedly say "Ha Ha, we must not allow these two to have children" but if they do it all before they get married it completely hoodwinks the spirits. Only the hardiest of these natives survive because at birth the mother has to appease the river spirit and sit in the river with her child for two days. As a result the rate of infant mortality is extremely high and only the very hardiest survive. In the tribe are the usual witchdoctors who periodically call a period of umah which means that the tribe has to build a communal dwelling house and during the construction of this house no sexual intercourse is allowed. On one occasion this led to their being a very long period of nearly eight years with no children and in fact the school on the island had to close down. The natives being so superstitious and the spirits being what they are it took many years to build this communal house because, for example, if a native is going to work carrying a bundle of poles and he sees a snake cross his path that is one of the worst omens and he will put his poles down and retire home for the day. So it is easy to imagine that as the island is full of snakes most days very little work would be done. During the period of courtship the young man builds himself a little house in a tree to which he takes the girl he hopes to win but he must always be home before daylight or his friends will laugh at him and that apparently is one thing these chaps cannot bear. The Mentawai live in the jungle in a most primitive way, feeding on monkeys and caterpillars etc, and using poisoned arrows to kill their meat. All the work is done by the women who also do the fishing while the men merely hunt and otherwise appear to hang around doing nothing'.

We made good headway with the repairs to our Bintang Dua but all the while I was exercising my mind to think of some way in which I could rid myself of the worst elements of the crew because I believed that the majority of the men were perfectly good chaps but I had at least six who were really bad hats and were the cause of most of our troubles. At last the brilliant idea came to me that 'rats always desert a sinking ship' and it occurred to me that, as our ship was not really seaworthy, the six rats I had in mind might well decide to leave us. With this in mind I called "all hands on deck" and I told them all that we had now finished such repairs as we could and I was prepared to make the attempt at crossing the Indian Ocean. I said I personally was willing to take the risk although I was doubtful whether we would ever reach India because I thought it quite possible that the boat was not sufficiently seaworthy to stand up to such a voyage. I also said that if there were men who did not care to take the risk now was the time to say so and they would be free to leave and make their own way as best they could. After some discussion, during which time I made it quite clear that I thought the risk was worth it but on the other hand it was a very great risk and might well end up in disaster, one of the rats spoke up saying that he doubted whether it was worth taking the risk and I said that the alternative was for him to stay here on the island where he would be perfectly safe at any rate until the Japanese arrived. Soon the other rats began to agree with the one who had spoken and in the end, to my great joy, all six of them decided not to make the trip with us but to stay on Siberoet and the last I saw of them they were paddling a sampan out of the creek presumably to go back to the village of Siberoet. I enquired subsequently, on my return to England, whether any of these men had arrived back after the war but none of them had so I do not know what happened to them and can only assume that they were drowned or were captured and died in captivity.

Now I had a crew of 20 and the atmosphere in the ship was unbelievably different. People began to work with a will and there was no grumbling. We then set forth again in the hopes of reaching Pulau Nias but the light wind was still from the northward and progress was extremely difficult and slow. After several days we rounded the north end of Siberoet and stood out into the Indian Ocean. We found our bamboo water containers were working splendidly and the water was as fresh as the day we had put it in there. We had by then slaughtered all our livestock and were down to a low standard of rations of dried beans and tinned food. About half way between Siberoet and Pulau Batu, which is in the doldrums, we were completely becalmed, lying idle with our sails flapping on a glassy blue sea with the sun blazing down on us. If one was out yachting or sunbathing it would have been rather fun but when one is trying to escape it is not so pleasant. While we were lying in this helpless calm we observed in the distance a small steamer which appeared to be coming towards us. We had no glasses on board, of course, and it was therefore not possible to see what flag she was flying until she was fairly close. Suddenly one of our merchant sailors with good eyesight called out that he could see she was flying the Poached Egg or the Japanese flag and we were very much afraid that it meant the end of our trip. Indeed as the boat approached it became obvious that she was flying the Japanese Flag. The Captain put two rounds across our bows, which was quite unnecessary because we were completely stationary.

He stopped his steamer a long way from us - obviously taking no chances - and lowered a small motor boat which came towards us. When the boat arrived we saw it was full of natives, much to our surprise, and not Japanese so we excitedly asked who they were and they said everything was OK because there were Dutch people on board the steamer. This seemed very odd to me and when the man in charge of the boat handed me a note I opened it and it read "Would the Commander of the sailing vessel please come aboard the steamer". I spoke to Capt Apthorpe and suggested that as he was the senior officer of the Bintang Dua that he and I should go across to the steamer and see what it was all about. We stepped into the launch and proceeded towards what was to be a most extraordinary conference.

On arrival at the side of the steamer we clambered up the rope ladder to be met on deck by a Dutch policeman who promptly searched us to see if we were carrying arms. He asked us to come into the main saloon where we met the Captain who invited us all to sit down at a table as he wished to speak to us. In each corner stood a Malay policeman a Tommy gun at the ready. I strongly objected to this and told the Captain I could not possibly discuss anything with trigger-happy Malay policemen pointing Tommy guns at me and requested him to call them off as we were unarmed and unlikely to be able to anything. He sent his policemen away and then told us why he was there. He said that the Japanese had ordered him to come to find us because a Chinaman, who owned the Bintang Dua, had told the Japanese that some soldiers had stolen it. Capt Apthorpe and I remonstrated with him and said it was altogether wrong that he a Dutchman could capture Englishmen and Australians all of whom were allies and hand then over to the enemy and in any case why was he working for the Japanese. His reply was that it made no difference, he had his orders and he intended to take us back. When I saw we were making no headway in this direction I suggested to him that we all stay aboard the steamer and make for India. This, he replied was impossible (a) because the steamer had insufficient coal and (b) because he had his wife and children ashore and he was not going to leave them. I tried every means of persuading him including asking him to let us go and forget he had ever seen us. He replied that he could not do this because he was afraid that members of the crew would inform the Japanese of what had happened and he would get into trouble. I said "suppose we refuse to agree". He said he would be very sorry but his ship was well armed and he would be obliged to use force. It is true that he was well armed, having about 10 Malay policeman commanded by a Dutch Eurasian police officer. We had no arms except one or two revolvers and a handful of rounds.

It was quite obvious we were beaten so I went back to the Bintang Dua in the launch and had to inform the members of the crew what had happened. After all we had been through this was a most heart-rending moment and I am afraid the tears rolled down my cheeks as I told them that it was all over because we had been betrayed by the Dutch and were to be handed over to the Japanese. We then gathered up what belongings we had together with all the food which we shared out to each man and were taken on the steamer which then towed the Bintang Dua back to the village of Siberoet. There the Captain left the Bintang Dua and we saw no more of her.

Most of the night Apthorpe and I stayed up on the deck trying to think of some plan of capturing the steamer as it seemed to us that as we were numerically stronger it might be possible to overpower the Captain and the Police officer and his men and take charge of the ship. We did not think it would be too difficult as by now the troops, as usual, had chummed up with the policemen and were down below teaching the Malays to sing 'On Ilkley Moor B'tat'. The only real difficulty would be the timing so that every member of the crew was attacked at the same moment and then after having grabbed the weapons we could probably force the Captain to obey our orders. We went down below to the men's quarters and put the proposition to one or two of the more senior ones. They were, however, doubtful and when we called a meeting at least half of the company were absolutely against it and this would have been a job that would have required the firm determination of every man in our party. Reluctantly therefore Apthorpe and I discarded the idea and just waited until we were taken back to Padang. We did, however, have the satisfaction of eating every grain of food there was on the ship including all the Captain's bananas. Early next morning our little steamer entered Emmehaven which is the harbour of Padang. This little harbour is equipped in every respect and is a natural deep water inlet surrounded by high mountains, the highest being 12,000'. It was a magnificent morning and it hardly seemed possible that we were on our way to such a grim future. When the ship docked along side the quay we were met by members of the Japanese army and taken to a house where lo and behold there was standing dear old Peter Morley. Our numbers were taken and we were rudely pushed into the prison camp.

Thus ended, on April Fool's day, 1942, a very exciting trip which with a bit of luck and a little more skill might well have ended in success but in any event we had won six precious weeks of freedom and had a great adventure on land and sea.

Part Two---Internment

Chapter 1---Prison camps

The camp in which we were interned was a Dutch army barracks which was obviously used for native troops, who formed the core of the army in the Dutch East Indies, so in many respects was of extremely primitive nature. This camp was shared by Dutch and British officers and other ranks of which the vast majority were Dutch or Eurasian. At this stage we four officers were separated from our men and ordered to go to the part of the camp which housed the British officers. Here I was allotted a space on the floor and told that was to be my residence. As it turned out there was an excellent crowd of officers in this building and I began to think perhaps it would not be too bad after all. We had only been there two days however when an orderly came round to say that all the officers and men who had just been brought in from the Bintang Dua should assemble immediately outside the Japanese office with their kit. We did not like the sound of this at all but picked up our belongings and reported at the Japanese office. Here we were fallen in and ordered to mount a large lorry.

We had not the slightest idea what was going to happen next except that it looked rather ominous and when the lorry drove off with us in it escorted by a Dutch police officer - the same one who was on the steamer - we certainly began to wonder what was going to happen. We had heard many spine-chilling stories of what the Japanese did to their prisoners of war and we were not at all optimistic. The lorry drove on and after a couple of hours began to climb the mountainous areas and suddenly stopped and we prisoners were ordered to dismount. Quite honestly I thought that at this stage we were going to be shot as we were on a mountain pass with a sheer drop beside a small waterfall and it looked to be the ideal spot to commit such a crime if the Japanese had wanted to. We stood there feeling rather nervous but we need not have done because in the event it turned out that the police officer only wanted to take a photograph of the waterfall and having done this we were ordered to remount the lorry and we were off again.

It was a lovely drive once we got over our fear and we went on up to another Army barracks in the mountains, 4400' up, where there was a most pleasant change in climate. Presently we arrived at the barracks of Fort de Kock which had been an outpost of the Dutch army for many years. Here again we were rudely shoved into the barracks and brought before the Japanese Sgt of the Guard and it was here that we had our first taste of Japanese methods. He shouted at us in an incomprehensible language and because we did not do what he told us we all received some corporal punishment. Finally he got tired of this and ordered us into various parts of the camp, the officers again being put into the Dutch officer's hut. In this case we were only 4 English officers and sixteen men in amongst several hundred Dutchmen.

At Fort De Kock I must admit I almost enjoyed life. The climate was most pleasant and we lived quite well, the Dutch having ample supplies of food and port wine and as our mess was a comparatively small one we were well looked after by the Dutch officers, most of whom were Eurasian, and I must say I found them extremely nice chaps. Later the following day we had a call from the Japanese Camp Commander who came to tell us the reason why we had been brought to the camp. We were taken there because we had been very naughty and tried to escape from the Japanese and because of that we were to be punished. He then asked us if we had anything to say and our spokesman, Capt Apthorpe, said he thought the Japanese had no right to bring us here because by escaping we were only doing our duty and that we should be sent back to Padang with the rest of the English troops. The Japanese Major, who incidentally was wearing no hat, an open neck shirt, trousers held up by braces, and carpet slippers, said he could not do that yet but if we behaved ourselves he would see what he could do. He was not a bad old stick and was obviously out to have a peaceful and quiet life and when Capt Apthorpe demanded more bananas he actually produced them. We did not realise how lucky we were in this camp and I only wish that the rest of the 31/2 years I was to spend as a guest of the Japanese had been as good as the two weeks we spent at Fort de Kock.

After these two pleasant weeks we were sent back to Padang where all of us including the Dutch were squeezed into the big barracks there. One afternoon while I was walking round the camp I was going through the Dutch lines and I was surprised to see a large wooden box with the name R Purvis written on it. Naturally this intrigued me not a little and I approached a Dutch officer I had made friends with and asked him who this chap Purvis was and he said " I will introduce you to him" and later on he came over to us and with him was a Eurasian youth, very nearly black, wearing spectacles but with a very pleasant expression. This chap he introduced to me as Rodney Purvis. I sat down on a seat and had a long talk to Rodney who was terribly pleased to meet an English officer of his own name and in fact he made a habit of introducing me to everyone as his namesake. Apparently his grandfather, one Thomas Purvis, had sailed from Glasgow and landed on the west coast of Sumatra in the state of Menang Kerbau in which is the town of Padang and there he was up to no good and ran away with the Sultan's daughter. In the state of Menang Kerbau the inheritance goes through the female line so this was a very serious thing for the Sultan and a great hue and cry followed while they made their getaway. After a while the Sultan, being very anxious to have his daughter back, contacted Thomas (don't ask me how because I don't know) and said that if he would return he would be pardoned, so back went Thomas and in due course begat Rodney Purvis's father who was, of course, a fifty/fifty Eurasian. In due course the son married a Eurasian girl and begat Rodney whom I met in this prison camp. We stayed in the barracks in Padang for several months with nothing particularly eventful happening except that we were all very new to this kind of life and were very hungry all the time. The difference between the Dutch half of the camp and the English was very noticeable. We had only what we stood up in whereas they had everything. Some of them were generous and helped us but for the most part they did not. One, Mynheer Havinga, was wonderful. He gave me money, clothes and friendship and I grew to be very fond of him and we stayed together for 21/2 years.

Suddenly orders came to send a party away. Nobody knew where it was to go but it was rumoured that it was to go to Burma to build a railway. Peter Morley, who was in charge of the British, had to produce a certain number of British to go with the vast majority of Dutch. Actually my name was on the list but just before I was due to leave I exchanged with another English Officer who thought he would like to go. Personally I did not want to go as I hate changes when things are not too bad and I always think 'a devil you know is better than a devil you do not know'. Having made this change I then stayed in Padang for another few weeks then we all had orders to move and there followed a most interesting journey to the north of the island. For this trip, which took 5 days, we were loaded into lorries, and we drove in these open trucks from Padang on the west coast to Belawen on the north east coast, which meant going right across the ridge of high mountains of central Sumatra. This was a trip which wealthy men would pay hundreds of pounds to do, in greater comfort its true, but here we were doing it for nothing. We started off from Padang and spent the first night at Sibolga, which is a small town on the coast 70 miles to the north and there we all slept in such buildings as were available and I personally was on a garage concrete floor - no mattress or anything. The following morning we were up early and started the drive across the mountains. We stayed at several places but the one I remember best of all was the night we spent in Tarutung which is a market town high up in the mountains. Here we were all put into the market which was enclosed by a wooden slatted fence and I remember we were ordered to bed down on the benches upon which the vegetables and meat etc would be displayed. While we were there, of course, the natives poked their heads through the fences and laughed at us but at the same time we were able to buy small luxuries such as lumps of Gula Melaka, which is brown treacly palm sugar, nuts and other such luxuries. The meal I remember best of all was eating a bread roll covered with margarine with my legs dangling over the cliff looking down into Lake Toba which I believe is one of the largest lakes in the world and certainly the highest. Throughout the trip there were always interesting things to see, particularly the house built by the Bataks. These houses are narrow at the bottom getting wider as they go up and roofed with a large over-hanging roof. They are very beautiful and have patterns in them that look rather like mosaics. This surprised me in view of the fact that the Bataks as a race are extremely dirty looking people.

On the 5th day we arrived at Gloegoer Camp, Belawen, which is the port for Medan, the capital of Sumatra, and we were put into barracks which were previously built by the Dutch to house their Javanese coolies. One hut was kept for the officers and there were 130 officers put into a hut normally reserved to hold 50 Javanese coolies. This meant that each officer had a space on the boards which ran down each side of the hut, with a gangway in the middle of about 2'6", and on that he had to live with such belongings as he might have been fortunate enough to bring into the camp. In these barracks I stayed for about two years. On the whole conditions in this camp were not too bad as there was running water and sufficient food which was well cooked, mostly by Dutch cooks. Once again we were a comparatively small English party in amongst a big majority of Dutchmen.

We had not been there very long when the first trial of strength occurred between the prisoners and the Japanese. Suddenly, all prisoners were ordered to parade outside the guard room. At that time there were about 1800 of us and we duly fell in before a small platform which the Japanese guard had just erected; a rumour had gone round that we were going to receive pay so we were all quite excited. Upon this platform came the Japanese Commanding Officer, a very tall, lean, bespectacled, Lt Col. He made quite a long speech in good English in which he welcomed all the prisoners and said how well they must have fought but unfortunately it was no use fighting the Japanese because they would always win. He said he hoped we would be happy in his camp and his one wish was to get us all safely back home when the Japanese had won the war. We listened to this for some time and then he said in his smarmiest language that he wanted us to sign a document in which we would promise not to escape. He told us that General Percival had already signed one such piece of paper and all the troops had done the same in Singapore and therefore there was no reason why we should not do so. Needless to say we did not agree, and our C.O. told the Japanese Colonel that we could not under any circumstances sign such a document and it was the duty of every prisoner to try and escape if he could. The charm soon left the face of the Colonel and his true colours began to emerge. After some wrangling he said bluntly "Very well, if you won't sign you will go back to your huts and stay there without food until you do sign" With that we were dismissed and ordered to go to our huts.

On the first day rations were duly brought to all the huts, of which there were about eight in number, and we sat down on our bed boards to pass the time as best we could. On the following day only half rations arrived and later a Japanese officer to enquire whether or not we would sign the form to which our reply was "NO". For the next three days no rations arrived at all and things were getting pretty bad. During this time a Japanese officer kept calling at the hut saying that other huts had signed the form and therefore we ought to do the same but our reply was still "NO". Finally, on the 5th day when all the other huts in the camp had signed our doctors got together and decided it would be foolish to hold out any longer as we might need our strength later on and that we had amply demonstrated our point and that if we went out to sign now we would be signing under duress and the signatures would not count. It having been decided by the Doctors, the senior officer in the hut, a Dutchman, told the Japanese officer on his next call that we were now prepared to sign the form but we were doing so under duress and that it would not count. Then followed the most extraordinary scene in which the Japanese Commanding officer and two or three officers and a number of troops came to the door of the hut and as we emerged they patted us on the back, handed us bunches of bananas and papayas and said what jolly good chaps we were holding out like this and how the officers had beaten all the others and what a jolly good show it all was. We were then handed these pieces of paper which we signed. I would not like to say what names everybody used but I certainly did not use Purvis. I think by this stage the Nip Colonel did not care a damn provided he got the forms with something written on them that he could hand in to headquarters.

Time rolled on quite unobtrusively for some while after this and the great problem was to find something to do. Many of the men were taken out on working parties on various jobs including moving a lot of wireless material from a warehouse. This was a very stupid thing for the Japanese to do when they forbade us to have a wireless because we had amongst us a number of clever chaps who could make a wireless out of anything and to put them in a warehouse with wireless parts was indeed a gift from heaven. Not long after this, those of us in the know had regular news bulletins from wirelesses hidden in all sorts of comic places. We did our best to organise ourselves and we had sports days, Melbourne Cup races with frogs, and we played cricket in a tiny space which had a little bit of grass on it, with a ball made of string and as there were a lot of Australians in the camp we were able to have Test Matches. We even played a little rugby football much to the amusement of the Dutch who thought we were quite mad!

The Japanese C.O. said they were going to give us a great treat. One of the sergeants was to be sent to Singapore to bring back Red Cross supplies. This was good news and for once they were true to their word. Several large crates appeared in the camp and under watchful eyes were unpacked in an empty hut. Such wonderful stuff - the Dutch were terrified we wouldn't give them any! - bully beef, milk, jam, and all kinds of tinned things. Every man received several tins which made a great difference to us. Unfortunately it was the only consignment we ever received.

While we were in Gloegoer Camp we were permitted to send a postcard home and a number of examples were given to us after being approved by the Japanese C.O. They were all very short and simple messages like:

'I am well, the Japanese are treating us very well, love to all at home'.

On one occasion, I think it was the second card, I decided to send it to my brother Raymond, with a coded message in mistakes so that he could see where I was. I sent the card addressed as follows: Doctor R M Purvis, "Weveday", 143, Archens Road, Southampton, England. The mistakes in the address read 'MEDAN' which is where we were in Northern Sumatra. The mistakes were: he has no initial M, the name of the house was "Waveney" and the road was Archers. The number of the house was 12 but my number 143 represented January 1943. I was very much afraid that the post card would never get delivered but by good fortune the post man used his head, but unfortunately nobody solved the mystery - they simply thought that I had gone round the bend!

We also had one delivery of mail and I received several letters from mother, members of the family and one from Pop Mead. These were a wonderful tonic. We were told that the Japs burnt most of the letters because of the impossibility of censoring them. All our communications with the Japanese were done through their interpreter - a funny little man who strangely enough had been to Glasgow University. On our side we had one Jap speaking Dutchman called Hamerslag.

We used to get into furious arguments with the Dutch about the loss of Singapore and the Dutch East Indies. During one of these a Liverpool sailor came along and put it very nicely. "At least we fought in Malaya and didn't allow the Japs to take the bloody place by telephone". Naturally this quite upset the Dutch but considering many of them came into prison camp with several cabin trunks full of goods I think there must have been some truth in it!

The food in this camp was not bad at all. We were always hungry, of course, but such rations as we had were well cooked and I thought very tasty. Our principal diet was rice with a little meat or fish. In the tropics there are lots of savoury things you can put in rice and frankly I enjoyed my meals - could have done with a bit more though. We were able to buy sugar and bananas from a Malay who was allowed in the camp each afternoon. We also had sufficient clothing and there was order and discipline - a thing we were sadly to miss later on. I was very fortunate to get a canvas mattress case off a Dutchman and more fortunate still there was a Kapok tree just outside the wall of the camp. One day a guard gave me permission to climb the tree and pick the seed pods. Apart from the fact that, unknown to me, there was a colony of huge red ants living there, it was easy to get these pods. The ants won when I fell out of the tree, but I got enough Kapok to stuff my mattress and sleep comfortably for many months. One day the Japanese Colonel said that if the officers cared to dig a garden and grow food we could have the produce in the camp as extra rations. We thought this was a splendid idea as we had quite a number of Dutch planters amongst the prisoners and it would also give us something to keep our minds occupied. Practically all the officers volunteered to dig a large area of land outside the camp and all in all we had 12 acres of land which was previously used for growing tobacco and had most beautiful soil. We worked hard for months and finally turned out a truly magnificent garden in which we grew almost everything you can think of, ground nuts, sweet potatoes, tapioca, peas, beans, bananas and papayas. After about three months the first fruits of our labours began to ripen but needless to say as soon as this happened the Japanese broke their word and sent all the fruit and vegetables to their own quarters. This caused a great outburst of wrath from all the prisoner officers and then the Japanese relented a little and said they would not take it all but whatever we had would be deducted from our rations. So, in the end, except for those who worked in the garden, the camp was no better off. I say, except for those who worked in the garden, because we worked a system whereby whenever we were in the garden we always ate as much fruit as we could although this was strictly disallowed by the Japanese and if you were caught it meant a beating up and then standing for several hours with a heavy papaya in each hand raised above your shoulder. This was a most unpleasant form of punishment particularly when carried out in a blazing sun. However, for the most part, we defied the Japanese and not many of us were caught and we began to be adept at smuggling food into the camp.

It was in Gloegoer that I met a very great friend to be, Sjovald Cunyngham-Brown (Crowded Hour 1975), a D.O from Malaya; a brave, artistic, blond northerner. He was wonderful company, having travelled the world, and we stayed together for the rest of the time.

About now we had a new Commanding Officer and our tall Colonel was posted elsewhere. His name was Captain Takahashi and he was really a very good chap indeed. He put a stop to all face slapping and also said that officers need not bow to Japanese troops, which up to now had always been the rule and if you failed to do it meant a beating up or pretty severe slapping. He told us that while he did not like us particularly he was going to see that we got the things we ought to have and that strict discipline would be maintained in the camp. This suited us very well and several months passed without any particular incidents occurring. Then came the time when Captain Takahashi was posted to Changi, Singapore and a Captain Meora came to the camp. He was not at all a pleasant person and with him we were obliged to give all our commands in Japanese and when we were being counted at roll call we had to number off in Japanese. Naturally enough this used to cause a great deal of trouble, because, believe me, it is extremely hard to number off in Japanese. You try to work out what your number is and then think what it is in Japanese but if you make a mistake and your number is not what you thought it was and it is called out by your next door neighbour, in the heat of the moment it is extremely difficult to think what the next number is in Japanese. As the man in charge of my hut I had to learn all these Japanese commands and it was not long before they became almost as natural as the English ones. Bowing to guards and face slapping and rifle prodding all started again.

During this stay in Gloegoer camp we had many industries working. One of the Petty Officers had a sewing machine and out of all sorts of rags he ran up some excellent clothing. Then there were various other members who made pipes and others who rolled cigarettes and put them into paper cartons for sale and all this time we contrived to pass the time as best we could. We were receiving pay by now - of Japanese home-made Guilders - but inflation was terrific and it didn't go very far. When the pay arrived each officer was supposed to sign for his by making his thumb print on the pay roll opposite his name. I used to accept the lot and sign for the others with all my finger tips and toes making lovely marks all over the page! The Japs used to deduct about 20% of our pay for board and lodging - damned cheek.

Chapter 2---The horrors begin

Eventually the day came when we were ordered to leave to go to Singapore. We were loaded up with all our belongings and during two years, even as a prisoner of war, you acquire certain things which seem precious and I had almost more than I could carry. I completely filled two large packs but things like homemade chairs etc, had to be left behind. We were driven off to Belawen and there put on board a small steamer. We were a party of about 750 of us.