|

|

![]()

| STORY OF "F" FORCE |

| The following article was passed to me by the 8th Division Signals Association around 2004. In 2009, the website owner received permission from the RSL Victoria to reproduce the article. |

Background:- "F" Force was a combination of 7,000 POWs (3,600

Australians and 3,400 British) sent from Singapore to Thailand in April

1943. Unlike most other groups it was forced to march to it's

work stations in Northern Thailand a distance of around

270km. The Force marched at night to avoid the day time

temperatures of over 40 degree C. They were often deep in mud

as the Monsoon had started. It is reported that the force had

no "Yasme" (rest) days and it is estimated that they worked for around

150 days straight. The Force was in the most remote area of

all Forces. Supply of food was irregular. They had

to carry personal effects and medical supplies. When the

railway was completed in October 1943 the remnants of the Force were

returned to Singapore. Around 3,000 (2,000 British and 1,000

Australians) died during the period they slaved on the Railway for the

Japs and their remains are in Thailand and Burma.

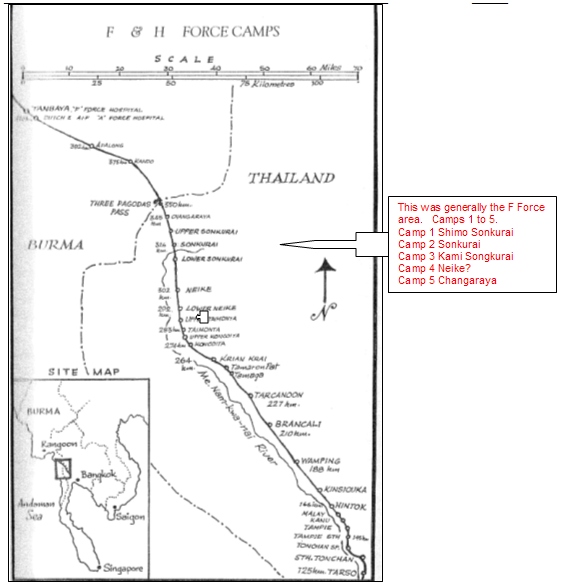

The above map was copied from Don Wall's book "Heroes of "F"

Force". Don's son Richard gave me approval to use material

from the book, as long as it was acknowledged. The book,

which is a valuable resource is still available.

PGW.

The above map was copied from Don Wall's book "Heroes of "F"

Force". Don's son Richard gave me approval to use material

from the book, as long as it was acknowledged. The book,

which is a valuable resource, is still available.

PGW.

The Victorian R.S.L. has granted permission to our Unit (8th Division

Signals) to print story of "F" Force as appeared in "Mufti" in 1951 -

3.

This article commences the story of "F" Force, a body of men from the

8th Division who were captured in Singapore, and lived for three years

as prisoners of the Jap. The story covers a period of eight

months in which the force was absent from Singapore.

This report provides an authoritative account of the activities of

3,662 A.I.F. P.O.Ws who, together with an equal number of British

prisoners, were sent to Thailand by the Imperial Japanese Army in

April, 1943.

The Malayan campaign had terminated on 15th February, 1942, with the

capitulation of Singapore, and from April of that year groups of

prisoners were despatched to Burma, Borneo and Japan, but as none of

these forces had returned to the prison camp in Singapore at the time

of writing of this report a comparison with the treatment meted out to

them is impracticable.

To the best of the belief of the narrators, however, the barbarism to

which the force was subjected had no equal in ferociousness and cruelty

in the history of other A.I.F. groups.

The purposes to which this report may be put at a later date are not

known, and to this extent the compilers are handicapped in that they

may fail to place sufficient emphasis on aspects which may become of

especial importance in the future.

They have endeavoured, however, to record faithfully and accurately all

the events, good or bad, which occurred in the eight months the force

was absent from Singapore.

Both the compilers were members of the force, and were either in

immediate contact with the commanders of the various groups (and the

Jap. Guard) or witnessed the conditions and happenings

recorded. (One of the compilers was commander of the A.I.F.

troops throughout the period and was in direct contact with the

Japanese commanders in practically all the camps and thus had personal

experience of all phases of camp administration and control; while the

other daily accompanied the men to work and gained first-hand knowledge

of working conditions on the road).

This report is based on: (a) The personal experiences and first-hand

knowledge of these two officers;

(b) Reports furnished by battalion commanders of the 27 Aust. Inf.

Bde., who acted as commanders of various camps;

and (c) The detailed log books that were maintained in all camps in

which A.I.F. troops were quartered.

The force comprised 7,000 men and was designated "F" Force to

distinguish it from the previous parties to depart. Within

eight months of the Force leaving Singapore approximately one half of

its members had died; of the remainder practically every man suffered

from one or more major illnesses, the full effects of which on their

future health can only be guessed at.

Some of the men have been incapacitated for life by the loss of limbs

and others have been permanently injured in mind and in body.

It will be established in this history that these results were brought

about by the ruthlessness, cruelty, lack of administrative ability,

and/or the ignorance of members of the Imperial Japanese Army.

The compilers, in fairness to the men, believe it necessary to say that

no word picture, however vividly painted, could ever portray faithfully

the horrors and sufferings actually endured. Incidents

occurred repeatedly in which the heroism and fortitude of the prisoners

equalled the highest traditions of the A.I.F. in war, but the written

word again falls short in conveying to the reader an adequate picture.

P.O.Ws were not fighting a tangible enemy but starvation and

disease. To the man who was starved to death the end was a

lingering one; to those who were struck down by disease -

from cholera, cerebral malaria or from any one of the loathsome Asiatic

death-dealing diseases, death often came quickly, but over every man

hung the pall of death, depreciating morale in all but the strongest.

Some of the finest men of the force, and, for that matter, of the

A.I.F., contributed towards their own illness, and in some cases

hastened their own death, by repeatedly trying to relieve the

intolerable hardships of their weakened comrades.

Camp commanders were frustrated at every turn. Efforts to

improve conditions, such as sanitation, were thwarted time and time

again with the result that the never-ending fight for lives gained no

relief at all.

Although it was not known at the time, the reason for the despatch of

the force from Singapore was to assist in the construction of a

railway, through the heart of the Thailand jungle, from Banpong to

Moulmein, for the most part following the route mapped out by British

engineers some years previously.

No accurate estimate of the number of P.O.W. and coolies employed on

the undertaking can be arrived at, but probably there were

150,000. The death rate amongst the A.I.F. men was lower than

that of the British or Dutch prisoners and of the vast army of coolie

labour that had been drawn from Malaya and Burma.

Deaths in the A.I.F. were 892, and an additional 31 died on their

return to Singapore, making a total of 923 known deaths at the date of

compiling this report.

This story will continue in serial form.

THE STORY OF THE F FORCE

Commenced last month, a history of the force sent from Singapore by the

Japs to work on the Burma railway.

It is a story of almost incredible hardships, adding weight to the

growing opinion that compensation to the utmost should be exacted from

the Japs and paid to the survivors of their brutality.

On 8th April, 1943, Hdqrs. Malaya Command was informed by the P.O.W.

Supervising Office at CHANGI Gaol that a working party of 7,000

medically fit British and Australian Prisoners was to be organised and

ready to move from SINGAPORE by rail commencing on about 16th April,

1943. The destination of the Force was not disclosed.

The reason given for the move was that the food situation in SINGAPORE

was deteriorating and troops were being moved to an area where food was

plentiful. At that time the rations issued by the I.J.A. were

extremely poor and the physical condition of even the fittest troops in

consequence was well below normal.

The following information was given by the I.J.A. :-

1. The

climate at the new location was similar to that of SINGAPORE.

Camps did not

exist and would have to be constructed on arrival.

2. The

Force would be distributed over 7 camps, each accommodating 1,000 men,

and

administered by an I.J.A. Commander and Staff directly under

command of General

ARIMURA,

Commanding P.O.W. in MALAYA, who was stationed at CHANGI.

All camps

would be in hilly country in pleasant and healthy surroundings.

3.

Sufficient Army Medical Corps personnel capable of staffing a

300-bed hospital could

be

included.

4. As many

blankets and mosquito nets as possible were to be taken by individuals

and

men

deficient in these articles and of items of clothing would be issued

with them on

arrival

at the new camps.

5. A band

would accompany each 1,000 men, and gramophones would be issued after

arrival.

6.

Canteens would be established in all camps in 3 weeks of the

completion of

concentration.

7. No

restrictions would be placed on the amount of personal equipment to be

taken;

Officers

could take their trunks, valises, etc., and men, all the clothing and

personal

effects

that they could manhandle.

8. Tools

and cooking gear, sufficient to maintain the Force as an independent

group, were to

be taken

and specific approval was given to include a field electric lighting

set for the

lighting

of the hospital and Force Hdqrs. Camp.

9.

Transport would be available for the cartage of heavy

personal equipment, camp and

medical

stores, and for men unfit to march. The latter concession was

granted when it

was

pointed out that a percentage of such men would have to be included in

the Force.

10. There

would be no long marches.

11. No

boot repair material could be issued at once, but a supply of the

necessary

materials would be taken

forward with the Hdqrs. of the I.J.A. Commander.

There can

be no doubt that the whole project was presented by the I.J.A.

authorities in

the most

favourable light, either deliberately or from a failure to ascertain

the true

position

in THAILAND, the destination of the Force.

A.I.F. Component

The A.I.F.'s quota was 125 Officers and 3,300 other Ranks (Combatants),

10 Medical Officers, 1 Dental Officer, 5 Chaplains and 221 other Ranks

of the A.A.M.C. Lt.-Col. C. H. KAPPE - then administrating

command 27 Aust. Inf. Bde. - was appointed to command the A.I.F.

component of the Force and Major R. H. STEVENS, 2/12 Fd. Amb. was

appointed Senior A.I.F. Medical Officer.

27 Aust. Inf. Bde., which had been kept intact since capitulation, was

to form the basis of the organisation, the quota being made up from

other units and services under the command of their own officers.

In effect, the A.I.F. component was raised on the lines of an Infantry

Brigade Group, a firm organisation that was the main factor in

maintaining the morale and discipline of the Australians at a very high

level in the months which followed.

Medical Situation

It soon was clear that there were not 7,000 medically fit men available

in CHANGI and this fact was notified to the I.J.A. After

discussion, Headquarters, Malaya Command was informed that 30% of the

Force could be made up of medically unfit personnel.

Lt.-Col. HARRIS - the Force Commander - was informed, in contradiction

of earlier advices that the Force was not to be employed as a working

party, and the inclusion of a high percentage of unfits would mean that

many men would have a better chance of recovery from ill-health in new

and pleasant surroundings where ample supplies of good food would be

available. A large number of British troops unfit for

marching or for work were included in the British component on this

understanding.

. . . To be continued

THE STORY OF THE F FORCE

Lt.-Col. Galleghan, C/O A.I.F., specified that only "near fits" should

be selected, Lt.-Col. Kappe pointed out that the original demand was

for 7,000 fit men for a working party, and that it was not in the

interests of the Force as a whole, or of the men as individuals, if

other than reasonably fit men were taken.

An effort was made by Malaya Command to have the strength of the Force

reduced, but this was not successful.

A medical reclassification of the Brigade was commenced

immediately. 1,569 men were found to be physically fit, 316

fit for duties in Changi, and 100 fit only for light duties.

The Brigade's quota was then reduced to 2,060, and the difference was

ordered to be made up by other units.

Definite figures of the medical examination of other units were not

available, but the A.I.F. component probably contained at least 125 men

who were unfit for work, and fit only to travel by train.

Of the British component, nearly 1,000 men were either fit for light

duties only or for travel by train. Many had been, in fact,

discharged from hospital to accompany the Force, a step that had dire

consequence. Man for man, the Australians were always above

the British troops in general physical conditions and stamina.

All ranks were vaccinated and inoculated against cholera and plague,

and tested for dysentery and malaria. The quick preparations

demanded by the Japs precluded personnel from receiving more than their

first cholera and plague inoculations, an incompleteness that became an

important factor later when a cholera outbreak occurred.

Every facility was afforded by Malaya Command to staff and equip the

Force so far as the existing meagre resources would permit. A

strong medical team was selected, which included surgeons, senior

physicians, an E.N.T. specialist, an officer with experience in eye

diseases, dentists and an anti-malariolist, with a special anti-malaria

squad.

Three months' medical supplies, based on normal expenditure, were made

available from the small reserves held by the British and Australian

hospitals, and it was assumed that there would be ample to maintain the

Force until Jap. supplies should be forthcoming.

A proportion of the Malaya Command's meagre reserve of clothing was

made available, but it was issued too late for distribution, and never

reached the troops.

Three days' reserve rations were taken, and these were of great value

during the train journey, and for the first few days following.

As it seemed likely that the Force would be concentrated in fixed

camps, preparations were made for entertainment, and the 18 Divn., and

the 27 Inf. Bde. Concert Parties were included in the Force.

The majority of the 18 Div. party died, as did three out of four of the

celebrity artists who accompanied the party.

The first train left Singapore on the 18th April, and the others on

succeeding days, the first six train-loads being composed entirely of

A.I.F. personnel.

The Force was distributed over 13 trains, each carrying about 500 and

600 men, according to the number of trucks reserved by the Japs. for

stores and baggage.

The trains were made up of steel rice trucks with no ventilation except

the sliding doors in the centre. The trucks were about 20ft.

x 8ft., with an arched roof 8ft. high (maximum), and to each was

allotted 28 men.

As on the majority of trains only one truck had been reserved for

stores, much of the stores had to be put into the men's trucks, which

were already overcrowded - so overcrowded, in fact, that only a few men

could lie down at any one time and none could even sit in comfort.

No halts for sleeping were made throughout the journey, and the men

were confined to their trucks for long periods.

The tropical sun beat continuously down on to the steel roofs of the

trucks, bringing the temperature inside to close to 100 degrees during

the afternoons. During daylight halts the conditions were

almost unbearable.

At the end of four days the men were utterly exhausted, a condition

made worse by the meagre meals of poor quality, issued at long and

irregular intervals. Very often the men were without food for

24 hours, and on one occasion there was nothing for 40 hours.

In any case, the meals comprised rice and a thin watery stew containing

a few onions only. On occasions a small piece of pork might

be found, but very rarely.

. . . To be continued

THE STORY OF THE F FORCE

After crossing the Malaya-Thai border, the I.J.A. Military Police

boarded the trains, and the concession of being allowed to detrain for

the purpose of defecating or for exercise was withheld.

No provision for sanitation had been made, with the result that the men

had either to defecate through the doorways whilst the train was in

motion or risk trouble with unreasonable guards by getting down at

halts without their permission.

At the places where permission was given the latrines were either

non-existent or were already completely fouled and

insanitary. The condition of these so-called latrines after

the passage of the train ahead was disgraceful.

For the whole five days of the journey men were unable to wash except

at Padang Besar, and drinking water was difficult to obtain.

On some trains men risked incurring the displeasure of the I.J.A.

guards by making billies of tea from hot water obtained from the boiler

of the engine.

One A.I.F. train was without any water at all from midday of one day

until nightfall of the next.

The Force detrained at Banpong, where it was quartered for one night in

a staging camp about a mile from the station. No transport

was available at the station and troops were ordered to carry as much

gear as possible with them to the camp. The short march under

heavy loads demonstrated how fatigued the men were by the train

journey. No. 5 train was most unfortunate as it lost nearly

24 hours in running time, and, in consequence, the party had to march

on the night of their arrival.

The day spent by the successive train groups in the staging camp at

Banpong almost beggars description. Conditions were

deplorable, and there was utter confusion.

The I.J.A. guards seemed to go crazy at their first experience of

directly controlling prisoners, and became well-nigh hysterical in

their efforts to deal with even a simple situation.

Everyone gave orders at once, and, as they were generally of a

conflicting nature, confusion increased, tempers were lost, and many

officers and men were struck for no reason other than that they were

doing their jobs and carrying out orders to the best of their ability.

Special cases of brutality will be cited later.

Each train commander on arrival was handed a copy of an instruction

headed "Instructions for Passing Coolies and Prisoners of War", which

was to be promulgated to the troops; this, together with the manner in

which the force was being treated, gave a good indication of what the

future held. It was here that the incoming train parties were

informed that they had to face a long march to the concentration area.

No provision was made for the transport of the medically unfit

personnel, and it was only with the greatest difficulty that the Japs

could be persuaded to allow the seriously ill men to remain behind.

The opinion of the Force medical officers was not considered to be

sufficient, and before a man could be admitted to the hastily organised

hospital his case had to be reviewed by Japanese medical officers, or,

in some cases, by Japanese N.C.Os.

Invariably the numbers which our medical officers considered were in

need of treatment and rest were reduced, and many sick men were forced

to commence the march.

The camp comprised four attap huts, built on low-lying ground, in a

very small area. Each hut had to accommodate 300 men,

allowing a space of 6ft. x 3ft. for each officer and man.

The water supply - drawn from a filthy well - was inadequate and

produced only sufficient water for cooking purposes and for one filling

of water bottles.

The meals were even poorer than those supplied en route from Singapore.

The huts and the adjoining area were in a filthy condition, and the

stench from insanitary latrines was overpowering. All train

groups made efforts to improve matters for succeeding parties, but the

indifference of the guards and the refusal to issue tools nullified

attempts to put the camp into a hygienic condition.

As previously mentioned, no transport was made available for the

cartage of heavy personal gear and stores from the railway station to

the camp, and all baggage had to be manhandled by men already exhausted

from lack of food and sleep. The officers' and men's kitbags

from the first two trains were taken to the staging camp where they

were stacked in the open and covered only by a tarpaulin. The

bulk baggage of the later trains was stored in a building in the town.

When it was announced that a long march was imminent and all stores had

to be carried, the men began to jettison surplus items of clothing -

those of poorer quality being thrown away and those of better quality

sold to the Thais, with whom there was a ready market.

A considerable amount of trading went on which was hopeless to check;

in fact, the Japanese guards themselves took a hand and enriched

themselves by acting as middlemen.

Although the selling of clothing generally is a matter to be deplored,

in this case the end justified the means, as thereby men were enabled

to purchase en route items of food to sustain them through a

particularly arduous period. In any case most of the clothing

sold could not have been carried.

So far as officers' gear is concerned, the story is different.

. . . To be continued

THE STORY OF THE F FORCE

Acting on advice received from the I.J.A., officers had taken with them

everything which they possessed, including personal effects which could

never be replaced. No guards were placed over the stack of

trunks and valises at the staging camp, and within a few days the whole

were looted.

Many officers lost all that they possessed, including valuable and

irreplaceable personal effects. The loss of this gear was the

direct responsibility of the I.J.A., and the officers concerned should

be recompensed.

The experiences at Banpong were to be only a sample of the

inefficiency, lack of sanitation, and cowardly treatment that the Force

was to experience in the ensuing six months.

There is no doubt that the treatment here - after five days of

exhausting train travel - adversely affected the health of many men to

such a degree that they were never able to recover.

Although conditions varied slightly in the different parties, general

conditions were the same both on the train journey and during the

subsequent 17 days' march.

Reference to the section dealing with the train journey from Singapore

indicates that every man in the force suffered considerably from the

effects of the journey, and could not be classified as fit to undertake

a heavy march.

It must be remembered that it was not merely the case of well-nourished

men suffering from the privations and discomforts of five days on the

train - quite a number of these men (30% amongst the British) had been

classified as "sick" before their departure from Changi, where all men

had been subsisting for 14 months on a basic diet of rice.

The staging camps mentioned below were uniform for all parties, the

time-table varying so slightly as to be immaterial.

After the initial mental shock experienced by each party upon being

informed that they would spend "the next few days" marching, spirits

rose and morale actually was high when the troops made final

adjustments to their gear, and set out from Banpong at 2230 hours.

The major difficulty experienced at the commencement of the march arose

from the necessity to allocate the medical equipment into six or more

panniers, and from the efforts made to see that the carrying of this

equipment would be equitably spread over each party.

A good, flat macadamised road surface and full stomachs from food

purchased from the natives at Banpong resulted in the first few hours

of the march being covered to the accompaniment of old marching

songs. By 0300 hours, however, spirits had fallen

considerably.

Practically all equipment had had to be improvised to some extent, and

rope or wire substituted for the regulation webbing straps; boots,

after months without repair at Changi were beginning to chafe and cause

blisters; socks already were wearing through; limbs that had to be

cramped for days on the train were becoming stiff at the 10-minute

halts in each hour of marching; and shoulders unaccustomed to carrying

loads, were becoming sore.

Dawn found the men really feeling the effects of the sleepless nights

on the train, and it was not until 0900 hours, in a blazing sun, that

Tamakan (Tarawa) was reached, 17 miles out of Banpong, by the first

party.

Tamakan consisted of a padang, shadeless, except for one roofed but

unwalled cement-floored building about ¼ mile from the river

Mai Klong.

A lengthy check parade took place on arrival, cooks and latrine digging

parties were detailed, and the men were told the next move would be at

2130 hours that night.

It was at this camp that the men first realised that they had to face a

future of a hard, combative existence, full of doubt, difficulties,

defeats, disappointments, and dangers.

By the starting time the majority of troops, fortified with meals of

eggs and fruit which they purchased locally, had regained some of their

spirits, but it was not to last. By midnight the tribulations

of the previous night had become accentuated, and by dawn it could be

seen that a number of men were in a bad way.

That the troubles were not more serious was due to the fact that for

the last two or three miles ox carts and tricycle-rickshaws were hired

to carry the medical boxes, gear, and many men who had been straggling

at the rear of the column.

. . . To be continued

THE STORY OF THE F FORCE

Kanburi (15 miles from Tamakan) was reached at 0800 hours, and a more

uninviting sight was hard to imagine.

One small open-sided shelter was all that was available as cover for

the sick, whose number by this time had increased

considerably. For the remainder, an open space with a few

stunted lantana bushes was allotted.

Inspection of the ground revealed that it had been used recently by

coolie parties which preceded the force, and, as usual, no attempt had

been made to provide latrine accommodation.

The result was that the ground was fouled in all directions, flies

abounded, and the stench was particularly offensive.

After areas had been allocated and latrines dug, the troops were

informed that no march would take place that night. As the

last two stages of the journey had been in heavy dust, many men took

the opportunity of walking another mile to the river to wash their

travel-stained and sweaty clothes.

Perhaps one of the greatest insults to the men was that the only

drinking water available close to the area had to be purchased from the

native keeper of a dirty well, at five cents per bucket, and then

boiled.

What might be termed a stocktaking then took place. Sick men

were classified, surplus gear jettisoned or sold to eager Thai

purchasers, medical gear distributed to be carried on the person

instead on in panniers, blisters and embryo ulcers were cared for, and,

as far as possible in the face of a heavy attack of mosquitoes, sleep

was taken.

It is worth noting at this point that throughout the journey repeated

check parades were called for by the Japanese guards. Almost

invariably these checks were ordered at the most inconvenient times.

If camp fatigues such as latrine digging, cutting and carrying of

firewood, drawing water had just been completed and the men dispersed

to their improvised shelters to endeavour to obtain a little rest, a

parade would be called, and the men kept standing about in a blazing

sun while order and counter-order was given by the numerous guards, all

of whom desired to exercise control of the check.

Upon awakening next morning, hopes for a day of rest were dispelled

when it was announced that a medical inspection would take place at

Kanburi Hospital at 1400 hours. One mile each way was marched

to the inspection - a wait of two hours ensued until the arrival of the

Japanese doctors - and then a remarkable speedy glass rod cholera test,

malaria blood test, smallpox vaccination, and two inoculations took

place.

On return to camp a hurried meal was eaten, gear repacked, and the men

were on the road again at 2100 hours.

The contract set for this stage of the journey was 15 miles to

Wampoh. It was on this march, more than later ones, that

officers, medical, and other personnel stationed at the rear of the

columns had their greatest trials. The number of sick and

stragglers was particularly heavy, ox carts and rickshaws no longer

were available, and the number requiring their gear to be carried for

them and physical assistance rendered trebled itself.

Some men were so completely exhausted that they had to be carried mile

after weary mile on stretchers, there being nowhere at all where they

could be left.

The pain and additional fatigue endured by those to whom fell the lot

of rendering this assistance to their comrades was extreme, and

undoubtedly the suffering thus caused reduced their own resistance for

later days.

After this halt every effort was made to keep the sick at the front of

the column.

Water points had been arranged by the I.J.A. for this march, and at two

places during the night water-bottles were refilled with hot

water. In spite of these marches being made at night, the

humidity was high - within a mile of the commencement of the journey

shirts were always sweat-soiled and drenched by intermittent rain, and

they remained so until morning.

The dust, arising from hundreds of feet tramping along a very dusty

track, settled on wet clothes and bodies, and made conditions still

more unbearable.

Wampoh, although nominally a staging camp, consisted of a flat stretch

of ground on the river bank, close to an old Siamese temple.

No buildings whatsoever were available. Two or three trees

provided shade for the sick, but for the rest it meant lying down in a

scorching sun, and being tormented by myriads of flies.

Itinerant food vendors set up their stalls in the area, and the men

were able to supplement the totally inadequate ration of rice and onion

water with food of some-what doubtful quality at times, but,

nevertheless, very acceptable to hungry and weary men.

Some parties succeeded at this camp in hiring a small amount of

transport for the heavy gear, the men subscribing one dollar each to

pay the price demanded by the Thai ox-cart drivers for the hire of

their vehicles.

The night's march, commencing at 2000 hours, was a heavy one.

The road surface was fast deteriorating, and hilly country was being

entered. By first light it was again found that many men were

seriously distressed. Diarrhoea had weakened many, and as

each day passed complete exhaustion among the less robust men became

more apparent. At 0830 hours the 15 miles had been completed,

and the objective, Wonyen, reached.

Once again all that the camp consisted of was a cleared patch of ground

with scattered clumps of bamboo, which provided an hour's shade as the

sun moved round. Ants and flies during the day made sleep

well-nigh impossible, but the troops were informed that there would be

no march that night.

A small amount of food was purchasable, but prices were rapidly

sky-rocketing, quality lessening, and the absence of cleanliness in the

vendors becoming very marked.

The night's rest again gave medical officers and orderlies an

opportunity to give more much needed attention to the sick, and when

the columns moved at 1930 hours the following day on a dusty, hilly

road, sprits had revived slightly. It was this night's march,

however, which proved conclusively that some men were unfit to go

further.

The outskirts of the base camp at Tahso (Tarsao) were reached at first

light, and working parties of men from "D" Force, which had left Changi

in March, was one of considerable size, and included a bamboo-hutted

hospital. After lengthy but unnecessary delays, the troops

finally were allotted an area, far from clean, and were issued with a

few tents as shelter from the sun.

Determined efforts were made here for the dropping at the hospital of

the seriously sick.

Lt.-Cols. Harris and Dillon and Major Wild, who were temporarily camped

there, were approached, and these officers made representations to the

I.J.A. for this concession.

A sick parade was held, and a certain number of men were classified as

unfit to continue the march. The Japanese N.C.O. to whom the

report was furnished stated that only a proportion would be allowed to

remain. This N.C.O., incidentally, had driven sick men in the

earlier parties on to the road with a stick.

Major Hunt, senior medical officer of the party, paraded the sick men

to the I.J.A. medical officer, who agreed with the classification.

When the party was being checked for the march before leaving, the

N.C.O. became abusive, and attacked Majs. Hunt and Wild with a heavy

stick, breaking a bone in Maj. Hunt's hand.

Chaplain Ross Dean, who was amongst those who were refused permission

to remain, died later at a staging camp from physical exhaustion.

After much argument only a comparative few of the sick were finally

allowed to remain.

. . . To be continued

THE STORY OF THE F FORCE

We ended with the men camped at Tahso where an effort had been made to

induce the Japs to classify the sick men as unfit for marching and to

admit them to hospital. The effort was not a success and only

here and there, where a man could not stand on his feet at all, was

permission given for him to remain. The others had to get

along as best they could.

The departure from Tahso was timed for 1930 hours.

Overhanging trees, pitch darkness, a rough and slushy track following

heavy rains, made the march of slightly under 15 miles a heavy one.

Unselfish help by exhausted men in helping the sick was very marked. On

each night's march from this point onwards it was found that at about

half the total distance to be covered, a Japanese post

existed. Hot water was available, and an hour's rest given to

enable a survey of the sick to be made and all stragglers brought in.

In a few cases, instances were reported of the men in the rear of the

column being struck by Japanese guards but, on the whole, no great

exception can be taken to the treatment of the stragglers.

But, at this stage of the march, the troops were warned of the danger

of Thai bandits attacking men straggling in ones and twos.

In one case a member of a column was attacked, but beat off his

assailant by a heavy blow with a filled water-bottle. In

another, one of the guards, with several of the troops, charged against

the Thais, one Thai being bayoneted and several others severely struck.

Warnings also were issued against tigers.

These two threats appeared to have a far greater effect on the guards

than on the marching troops, and the guards repeatedly showed an

inclination to push themselves into the middle of the column rather

than be left at the rear with stragglers.

Kenyu (Konyu) was reached at about 0800 hours and, in contrast with

other camps, it provided some shade, being in the centre of heavy

bamboo clusters.

Washing facilities here were bad, and consisted only of a small stream,

in which a number of Japanese guards took strong exception to prisoners

washing while they were in the vicinity.

From this stage onwards troops began to suffer seriously from the

shortage of rations. Previously the extremely poor supply had

been augmented by purchases from wayside vendors, but having now

entered continuous jungle, kampongs were not seen, and facilities for

the purchase of food no longer existed.

By this time a further difficulty had arisen through the number of men

who now were barefooted. In addition, many who were still in

possession of boots found that their blistered feet were so badly

infected that the chafing of the leather made the wearing of boots

impossible. The rough gravel of the jungle tracks and fallen bamboo

made every step a painful operation for those in bare feet.

Following previous practice the departure from this camp was made in

broad daylight, and the 12 miles to Kinsayo (Kinsayok) were covered

before daybreak.

Although each of these staging camps bore names, all that could be seen

(until Takanun) was a clearing in the jungle with possibly one or two

Japanese tents.

The exhausted marchers flung themselves on the ground in the dark,

still wearing their saturated clothing, and it was not until the heat

of the day brought out ants and insects that they worried about the

usual meal of rice and onions.

A further night's sleep was allowed at Kinsayo, and the next morning a

check revealed that the rate of casualties was being maintained and

that soon every fit man would be carrying a sick man's gear as well as

his own.

Enquiries from the Japanese guards as to the total distance still to be

covered showed that the guards themselves were ignorant of the

destination.

The nights had become grim endurance tests, and even the fittest of men

were suffering severely.

The next stage was a 14 mile march to Wopin, and here the troops were

herded into a rough stockyard. Primitive latrines had been

dug by preceding coolie parties and left uncovered, to become prolific

breeding grounds for millions of flies.

On arrival at the next camp, Brangali (13 miles), conditions became

even worse. The Nippon guards in charge of the camp took

control of the troops immediately on their arrival, and the written

instructions headed "Conditions for Passing Coolies and Prisoners of

War" were again read to all troops.

The men were regimented from the moment of arrival until their

departure, and on the slightest breach of instructions they were struck

with heavy sticks.

In one case an officer, not understanding an order given in Nipponese,

was struck with a stick about the face and left standing at "Attention"

in the sun. After about a quarter of an hour he fell forward

in a faint and cut his lip badly, which caused general amusement

amongst the guards.

After departure this camp became known as the "Hitler Camp".

It was now raining almost every night, and to the difficulty of finding

the track in the pitch darkness was added the steepness and slippery

nature of the surface, which caused injuries to limbs.

Men fell from unfenced or undecked bridges and over

embankments. Sometimes the bridges were so rotten that men

fell through them into the streams below.

Another danger was met with here - the risk of losing men at the 10

minute halt.

The moment the order was given for the rest, men would cast off their

packs and, wet or otherwise, fall on the ground completely

exhausted. When the order was given to move again it was

impossible to tell in the darkness whether all the men had heard the

call, and on more than one occasion parties had to return a mile or so

to pick up missing men - a happening that did not tend to improve

relations with the Japanese guards.

The site for the bivouac at Takanun was one of the best

visited. A cleared space on the hill, unfouled by previous

parties, with a clear, fast-flowing stream and plenty of shade, gave

the men

an uplift. Also a small issue of tinned vegetables, in

addition to the rice and onion water, improved their morale.

The move from Takanun was made in the late afternoon, along a road

inches deep in powdered dust. The column passed a camp of

British soldiers who had for some time been engaged in bridge

building. Although only ten miles away, Tamarumpat was not

reached until first light.

The men settled down to sleep, but flies, ants and mosquitoes made this

difficult during the day, although this particular resting place was

comparatively well shaded.

From the party, which then comprised part of Train 1 group (half of

this group had been left behind as cooks at staging camps or had become

too ill to march) and Train 2 group, orders were received to organise a

party of 700 to move to Koncoita, where they would be permanently

established.

Departure from Tamarumpat of this party was at 2000 hours, and the

troops were informed that the march was one of seven miles only.

Accustomed by this time to judging distances, the men were naturally

disgruntled when it proved to be about double that distance.

The I.J.A. guard, also under the impression that the march was to be a

comparatively short one, set a very fast pace and allowed no halts

except after an hour's marching. At about 2300 hours the

party arrived, completely exhausted, at a bivouac site which was

thought to be the final destination. It was then ascertained

that an error had been made, and that a further eight miles had to be

covered. This extra stretch was completed by 0800 hours in

the morning, after the troops had rested from 2400 until 0500 hours.

No water was available throughout the march.

The camp - Koncoita - was the first one that could be properly called a

staging camp.

It was at Koncoita that the Commander, A.I.F. Troops, contacted the

Force Commander, Lt.-Col. HARRIS, who was unable to give any

information as to the ultimate organisation and location of the train

groups as they came forward. He and his staff had travelled

forward with the I.J.A. commander by motor transport, but they had been

unable, through lack of prior information, to take any action to

ameliorate the conditions that the troops were to encounter.

Lt-Col. Harris stated that it was evident the arrival of the troops in

the concentration area had been too premature for the local

administration - if any such organisation existed at that stage - and

that conditions would not be very comfortable for the first three or

four weeks. He had been pressing for the establishment of

canteens and other amenities as soon as possible, and realising that

the rations en route had been very poor, he also was urging the

purchase of oxen in order that the men would at least get a meat ration

before work commenced.

The Force Commander continued throughout the ensuing six months to

press for better rations and canteen facilities but, as will be shown

later, his efforts met with very little success.

That the arrival of the Force was premature was amply proved by the

lack of preparation.

No meal was provided until the cooks drawn from the ranks of tired men

had prepared the usual watery onion stew and rice. No cover

was available, and men were compelled to lie out in the open in a

scorching tropical sun until nearly 1100 hours.

After some delay an issue of drinking water was made, but water-bottles

were not filled again until nightfall.

Shortly after arrival the battalion (from now on this party will be

referred to as Pond's Battalion) was informed that cholera had broken

out in the camps in that area, and that swimming in the river and

drinking of unboiled water were forbidden.

It was not until the battalion moved from its exposed bivouac to the

camp area proper that it realised how serious the situation really was

there.

Only a few huts were unroofed, and these were occupied by Ramil and

Burmese coolies. The battalion was first allocated an area

covered with vomitus and excreta, and after partially clearing this

area was ordered to a fresh site which comprised a few unroofed huts.

Everywhere there was evidence of the effects of an epidemic, natives

were lying about in various stages of death, and it was learned that

already there had been many casualties.

. . . To be continued

THE STORY OF THE F FORCE

Prior to moving from the bivouac area, the battalion had been addressed

by Col. Asami, the Chief Engineer of the area, who said that the

Australians had a reputation for being good soldiers and workers in

Singapore and he hoped that they would continue to act as such under

his command.

In conclusion, he made special reference to the necessity for good

hygiene and of every man looking after his health. He then

introduced Lieut Murayama as the future camp commander.

The I.J.A. administration of the battalion was in charge of a Japanese

sergeant who, it was thought, took his orders direct from Lt.-Col.

Banno, Commander Prisoners of War, Thailand. After some

delay, drinking water was issued, but in such small quantities that the

men remained thirsty until nightfall, by which time the battalion

commander had been able to make his own arrangements.

On the morning of 11th May, Lieut. Murayama ordered that a detachment

of 100 men move to the next camp, about 4 ½ miles further

north where they would work on road reconstruction.

Orders also were given to the effect that all fit men were to commence

work on the road in the vicinity of Koncoita on the following morning.

It was pointed out to the Japanese sergeant in charge of administration

that all the men were in need of rest, and that as many as possible

should be employed in the camp establishing proper sanitary conditions

by digging latrines and cesspits and clearing the area of

excreta. There was need, too, to construct a reasonable

cookhouse and water sterilising points, but protests were of no

avail. The Japanese N.C.O. reiterated the order that all but

the sick must go out to work, as would all officers.

Lt. Cols. Kappe and Pond were to go out on successive days.

There seemed to be no fixed policy as to the inclusion of officers in

working parties. Throughout, Murayama demanded that all

officers, excepting one administrative officer, would accompany working

parties, while in some camps the Engineers permitted one officer for

each 100 men, and yet in another they stated on more than one occasion

that no officers were wanted.

It is not to be thought that the lives of the officers were to be soft

and comfortable. In all A.I.F. camps they were utilized in

sanitary squads, on wood cutting and carrying parties, on ration

parties, and on essential duties within camp hospitals.

During the next five days Pond's battalion was engaged on road building

and bridge construction. It was during this period that the

succeeding train parties began to pass through to the north after

stopping at Koncoita for one night's rest.

Most of the parties had to contend with heavy rain, in addition to the

other trials of the march, and were in very poor condition,

particularly the British troops.

The accommodation became overtaxed to the extent that the on-going

troops were quartered within 100 yards of the huts occupied by the

coolies, who were lying about exhausted by dysentery or some such

disease. Efforts were made to improve the sanitary

conditions, but with the shortage of tools and labour it was impossible

to deal with the fly menace effectively, especially when the main

breeding places were outside our control. Because of the

failure of the I.J.A. to force the natives to clean their area of

excreta and filth generally the Force as a whole was to suffer

unbelievably in the next few weeks.

That the position was precarious was evident to Lt.-Col. Kappe and

Major Stevens, the Senior Medical Officer, A.I.F. The former,

therefore, asked, through the administrative sergeant, for an interview

with Lieut. Murayama, so that the position could be placed before

him. No answer was received to this application or to the

many other requests of a similar nature made later.

Failing to obtain any satisfaction from the Engineer Officer, the two

A.I.F. officers called on the local I.J.A. Medical Officer (Lieut.

Onoguchi) and made requests based on medical grounds for more tents to

protect the men from the weather and for the isolation of dysentery

patients, for medical stores and additional food for the working men,

and for a supply of rice polishings to combat beri beri, which had

begun to make itself manifest.

Lieut. Onoguchi stated that he had no supplies, but would do what he

could to obtain extra tents. The information that the local

authorities had made no provision for medical supplies came as a great

shock. Apparently the prisoners were to be permitted to die

in a similar manner to the natives in this camp.

The general situation was reported to Lt.-Col. Dillon and Major Wild of

Force Headquarters, when they arrived. They promised to

ventilate the whole position to Col. Banno when they reached

Headquarters Camp at Lower Nieke.

On 14th May a request, written this time, was made to Murayama for

consideration of the matter of accommodation, food, including rice

polishings, boots, medical supplies, rest days for the workers, and

canteen supplies. This request met with the same fate as the

verbal ones.

Both the Force Commander and the Commander A.I.F. troops continued to

press these matters right up to the time the railways tasks were

completed in October. It was only in that month that five

bags of rice polishings were issued.

The food remained bad, canteens were never established, medical

supplies were received in meagre quantities only, and except for minor

issues of boots and clothing, the bulk of the Force remained bootless

and, in some cases, almost naked.

On 15th May, it was announced that Cholera had broken out amongst the

coolies and, that next day, the battalion would have to move and join

the detachment at Lower Taimonta.

On the 16th May the battalion went out to work as usual, but instead of

returning to Koncoita pushed on to the new camp, which was newly

constructed, although it had previously been occupied. As at

Koncoita, the huts were unroofed and still insufficient tentage was

available to cover more than two-thirds of the battalion.

It was thought that the initial distribution of troops as decided upon

by the I.J.A. was to be spread over four camps, comprising:-

. Pond's

Battalion of 700 A.I.F., located at Upper Koncoita, and subsequently

moving

Northwards on road improvement;

. A main

British camp of 2000;

. A main

A.I.F. camp of 2500; and

. A mixed

Headquarters and Hospital Camp of 1300.

This arrangement was varied to meet the situation which the Force was

competed to face.

THE CHOLERA OUTBREAK

It was on 15th May that the I.J.A. medical authorities diagnosed as

cholera the disease which was causing a high mortality amongst the

coolies at Koncoita. Because of this, Pond's battalion was

hurriedly moved forward to Upper Koncoita.

On the night 14th/15th May, 1,000 A.I.F. from Trains 3 and 4, under

Major Tracey, marched out from Lower Nieke to their permanent camp at

Lower Songkurai, a distance of 7 ½ miles. This

party was to be joined by a further 800 A.I.F. in two days' time.

It was whilst the latter group was being organised that one of the sick

men was diagnosed by Capt. Taylor, A.A.M.C., as a cholera case.

The Force Commander reported the fact at once to Col. Banno, and

recommended to him that all movement of the Force be stopped in order

that those troops which had not yet come into the cholera zone, i.e.

Koncoita-Lower Nieke should be saved from infection.

The request was refused, and the party referred to above, moved out

from Lower Nieke on the night 16th/17th May. Prior to doing

so, volunteers were forthcoming to staff the improvised isolation

hospital, which had been established in a portion of an unroofed hut.

By the evening of 16th May three more cholera cases had been diagnosed,

and it was certain that many other members of the Force had become

infected.

Due to the Japanese refusal to permit of any reallotment of key

personnel and the transfer of officers from one train group to another,

only one medical officer was available at Lower Nieke. An

urgent message was sent to the Senior Medical Officer, A.I.F., who

decided to go forward himself and take with him Major Hunt from

Koncoita, and Capt. Hendry, from Upper Koncoita.

. . . To be continued

THE STORY OF THE F FORCE

Due to the bogging of the ambulance in which they were travelling, the

two senior officers had to march most of the journey through the mud,

and arrived at Lower Nieke at about midnight on 16th May.

There they were greeted with a rumour that cholera had broken out at

Lower Songkurai and that the only medical officer there (Capt. B.L.

Cahill) was seriously ill.

It was decided that Major Hunt and Capt. Taylor should move on to Lower

Songkurai that night. The medical officers, accompanied by 7

A.A.M.C. personnel and 8 British volunteers, all of whom had been

doubly inoculated against cholera, arrived at 0230 hours on 18th

May. Cholera had actually broken out, two cases having been

diagnosed, but Capt. Cahill, although exhausted, fortunately otherwise

was well.

To appreciate the difficulties which medical officers and senior

combatant officers had to face during the ensuing who months the

following factors must be borne in mind:-

1. Officers and Men were almost exhausted

after an arduous train journey, a brutal march

for men who had undergone fourteen

months' imprisonment on poor rations and the

lack of any sustaining food provided at

any of the deplorably filthy staging camps.

2. Many men had become desperately ill on

the march with severe attacks of diarrhoea

and dysentery. Men not so

affected themselves had lowered their resistance to disease

by the physical efforts they made in

assisting their sick comrades along and carrying

their gear.

3. As soon as parties arrived in their

final camps they were immediately set to work on

road and railway construction.

4. The unfinished condition of the camps

on arrival, and the inhuman attitude of the I.J.A.

Commanders.

LOWER SONGKURAI CAMP - NO. 1

To call this place a camp at the time of arrival of our troops is a

misnomer. Accommodation consisted of two lines of bamboo huts

running parallel to the road at the foot of a steep hill, covered with

bamboo and the debris from the construction of the huts obviously

several months previous.

Except for 8 tents to cover the officers' quarters, no protection

overhead had been provided. The exposure of the unroofed huts

to tropical weather had put them in such a condition that in most cases

they were almost in need of demolition and reconstruction.

Latrines had been dug on the hillside above the huts, and consisted of

only two banks of wide, shallow trenches, obviously a menace to

health. Kitchen accommodation did not exist, and the water

supply was so meagre that ablution was impossible.

No hospital accommodation had been provided for. The huts

comprised either 18 or 20 bays, each measuring 10 feet x 12 feet in

which 10 men had to sleep.

It was obvious that it would be impossible to accommodate the 2500

A.I.F. destined for this camp, and representation to this effect were

made to the I.J.A. Supervising Officer who, apparently, send on only

the balance required to make 2000 and reallotted the remaining 400

A.I.F. in the forward area to No. 3 Camp, about 6 miles further north.

This was almost the sole occasion when this particular Supervising

Officer took heed of any of our requests or recommendations.

The first group of 1000 had arrived on the morning of 15th May, and on

16th May all fit men were sent to work.

The following day the second group, under Major Johnston, marched

in. After a survey of the camp, Major Johnston pressed for

the immediate supply of attap for roofing the huts in view of the

approaching monsoonal season, and stressed the necessity of keeping

sufficient men in camp to construct new latrines, kitchens, water

sterilising points etc., and for the reinforcing of the huts.

The floors of two already had collapsed under the weight of sleeping

men, and same showed signs of complete collapse within a week or two.

It was requested that, as a matter of immediate necessity, every effort

should be made to bring forward more medical officers and sufficient

serum to complete the inoculation of all troops against cholera, many

having been only partly inoculated before leaving Changi.

Lieut. Fukuda displayed some energy in endeavouring to meet these

requests, as he was to do when another cholera epidemic broke out in

one of his camps, but it was apparent that his greatest incentive was

the fear of contracting the disease himself.

He linked the arrival of Major Johnston's party with the outbreak of

cholera, and, despite protests, persisted for several days with the

view that only this party was affected.

This officer was to display the same lack of commonsense during a

second outbreak of cholera, which will be dealt with later.

Early on the morning of the 18th May, Major Hunt, who, with Capt.

Cahill, had arrived during the night, inoculated 1400 men with

½ c.c. of vaccine from limited stock he had been able to

pick up at Koncoita and Lower Neike. This vaccine had been

brought forward from Changi.

Steps were taken to establish an isolation centre and hospital for

general cases. The isolation centre which, at one particular

period was to house 128 patients, consisted of tents and marquees

erected on bamboo stagings.

The construction of this centre was carried on in incessant rain, and

it was only as a result of superhuman effort that the accommodation was

completed.

From the beginning, camp workers were hampered by a grave shortage of

tools, which were held by the Engineer Unit in charge of railway

construction, and issued for use only in limited quantities.

The Engineers right throughout were not in the slightest degree

sympathetic to any requests made in connection with camp sanitation and

improvement, and in many instances they deliberately obstructed the

work.

On the 18th May, Col. Banno arrived in the camp, and immediately called

a conference, at which Lieut. Fukuda and Majors Hunt and Johnston were

present. In the course of the discussion, Banno intimated

that the responsibility for checking the spread of cholera and for the

health of the men would have to rest with the Camp Commander and the

Senior Medical Officer.

With attempting to avoid the responsibility for the welfare of the men,

it was claimed that this was most unfair, in view of the condition of

the camp on arrival of the force. At the same time, the Camp

Commander maintained that the well-being and health of the men had

always been his first care.

Majors Hunt and Johnston raised again the question of the supply of

more serum, attap for roofing of huts, boots, medical stores and

cooking facilities. Col. Banno promised a few more tents, but

was completely non-committal on the other things.

That evening the Senior Medical Officer addressed the men on the

precautions that would have to be taken to prevent the spread of

cholera and other diseases. Many of the men hardly listened -

they seemed numbed mentally by the strain of the long march and by the

dread of cholera.

It was a few days before they recovered sufficiently to exert

themselves to meet all the demands made upon them.

There is no doubt that the forceful leadership displayed by Majors

Johnston and Hunt were the cause of the Lower Songkurai Camp eventually

becoming the most hygienic and possessing the highest morale of any "F"

Force Camp. The employment of all spare fit officers on works

and hygiene was a big factor in maintaining a standard of morale that

was to become an important factor in the fight for life in which nearly

every member of the A.I.F. was to become involved during the next few

months.

Within the next few days, 70 tents and loads of attap were delivered

into the camp, and shelter from the rain and heat of the day became

possible. After having spent several miserable nights in the

open, the troops found the cover most welcome.

By the evening of the 19th May, the inoculation of all ranks had been

completed. It was pointed out repeatedly, however, that the

inoculations were insufficient to give complete immunisation.

When the epidemic flared up eight days later, many lives were lost

through the failure of the I.J.A. to produce adequate supplies of serum

for a second inoculation.

The urgent need for a second inoculation was constantly urged --- as

was also the need for supplies of disinfectants, lime, blankets and

mosquito nets, all of which had been promised before the Force left

Changi.

During these strenuous and worrying days the Camp Commander and his

staff were continually being harassed by the instructions received from

Lieut. Fukuda - instructions that can only be described as "panicky" in

nature. In addition, they were generally futile.

As was customary with this section of the I.J.A. Administration, every

individual member of the Korean Guard believed himself empowered to

give instructions, which he invariably expected to be obeyed instantly.

Men were detailed for some minor duty, notwithstanding that they were

already carrying out a previous Japanese order, or engaged on some

vital camp work. The completion of essential works was

hampered by these extra orders, and bad feeling was engendered.

It was never possible for any Commander under Lieut Fukunda's

supervision to receive orders from a central source; he would never

permit discussion, and he refused to listen to complaints of any sort

made against the attitude of his men.

An example of the stupidity of this officer's decisions was his way of

segregating the two main parties in the camp.

The segregation was effected by the erection of a dividing fence, but

latrine accommodation still had to be shared, despite the fact that

both parties had had cholera cases.

To make matters worse, the creek in the camp was placed out of bounds

for ablution purposes, increasing the difficulty of maintaining a

reasonable standard of cleanliness and hygiene, a standard that was

particularly necessary because of the muddy condition of the camp

caused by the incessant rain.

On 20th May a part of 163 men marched in, bringing the camp strength up

to 2000.

At this stage 600 men were being provided for work on the roads, but

next day the demand jumped to 1300. There were 88 men in

hospital, and of the men in the lines, 327 were unfit for any duty, and

70 were fit only for light duty.

After 260 officers and men had been set aside for camp duties,

including medical staff, only 1218 of the required 1300 could be sent

out to work.

This caused the first of many stormy sessions between the Camp

Commander and the Supervising Officer. At first the latter

threatened to send out men regardless of their physical condition, but

the strong protests made on behalf of the men reduced the demand to

1220.

Rain was falling continuously, yet men were called upon to work 12 and

13 hours a day in an attempt to improve a road that had become

practically impassable. The strain of this, together with the

lack of cover at night and the loss of sleep occasioned by late meal

hours, plus the necessity of cleaning off mud and drying clothes in

front of hut fires, quickly impaired the health of the men, and some of

them began to collapse at their work.

Up to the 24th May the cholera outbreak seemed to be reasonably under

control. Only 20 cases, of which five were fatal, had be

diagnosed. On the 24th, however, the secondary wave of

infection, i.e. the infection contracted since arrival at the camp,

began to manifest itself.

. . . To be continued

THE STORY OF THE F FORCE

The dreaded cholera was a nightmare to the officers of the camp, and

the medical officers were powerless to check it's oncoming.

The ground between the camp latrines and the nearest huts was

frequently contaminated with faeces and vomitus of men unable to reach

the latrines in time.

The incessant rain swept infected material under the huts and along the

drains which passed through them.

Contact with boots, with patients direct, flies, and the lack of covers

for food, all played a part in spreading the infection despite

desperate efforts to localise it.

Deaths on succeeding days in the second cholera wave were 4, 4, 10, 11,

10, 4, 8. Total 51.

The crisis produced an hysterical reaction on the part of the I.J.A.

Camp Staff and once again the responsibility for arresting the epidemic

and for checking the general increase of dysentery and malaria was

placed upon the Senior Medical Officer. It took these crises

to obtain supplies of serum which had been asked for on so many

previous occasions.

The lack of tools, and the men to use them, and the exhaustion of the

men on return from outside work had retarded all latrine and drainage

construction, and the failure to complete the works programme had

prevented the Camp Commander from achieving the standard of hygiene

necessary to limit the spread of cholera and dysentery.

After many protests, Lieut. Fukuda at last acquiesced in permitting 300

fit men to remain in camp for 3 days on necessary works, but conditions

had by then become appalling, and only firm control and the highest

discipline could stem the tide.

It was at this stage that Major Bruce Hunt made an impassioned and

dramatic appeal to the men, which finally dispelled the lethargy that

had been so apparent, and imbued the men with a new spirit of

determination to fight the crises out. It was one of many

such addresses that Major Hunt gave at this and other camps, all of

which had an enormous effect on the morale of the Force.

The Senior Medical Officer, A.I.F. (Major Stevens) had taken seriously

ill at Lower Nieke Camp, and therefore was unable to take over medical

control.

An extract from Major Johnston's report is quoted here to indicate the

manner in which the troops responded to the inspiring leadership and

example of the Senior Medical Officer (Major Hunt) in the camp:-

"It can proudly be said that this most terrible crisis in the

experience of the 8th Division found the high morals of the men of the

A.I.F. a dominant factor. Such crises produce the best and

the worst in men, but it is always the best that will be remembered

when the cholera epidemic at Lower Songkurai is called to mind.

The spirit and self-sacrifice displayed even in the performance of the

most menial tasks was beyond praise, but praise alone cannot replace

the loss of several lives among the volunteer medical and cholera staff

during this period."

On 29th May, the third day of the period Lieut. Fukuda had promised

would be allowed for the completion of hygiene and other camp works,

the assurance was broken, and a demand made for 750 workmen, on the

orders of the Engineers.

All protests were unavailing. With the cholera crisis at its

height, it was decided to frame a strong protest for submission to Col.

Banno.

The medical situation was grave, cholera was raging, and dysentery and

malaria were on the increase, and it was estimated that within a month

only 250 men out of 2000 would be fit for work.

800 men had become invalids and the number was steadily

increasing. Demands were made that work on the railway should

cease indefinitely. Demands were made also for medical

supplies, blankets for the sick, invalid foods, improvements in

rations, suppressive atebrin, more water containers, waterproof tents

and oil to deal with mosquito breeding areas.

A memorandum sent to Col. Banno concluded with the following:-

"As soon as the health of the camp has been improved, which may not be

for several months, the evacuation of the area by the troops and their

subsequent treatment in a manner more befitting the honourable Japanese

nation whose reputation must suffer gravely if the present conditions

continue, is demanded."

The memorandum was translated and forwarded to I.J.A. Headquarters and

to the Force Commander, who endorsed its contents. The

context of the demands were also forwarded by that officer to Lt.-Col.

Kappe, who, despite many requests, was not permitted to leave Pond's

Battalion and go forward to the main portion of the Force. He

was himself in the process of framing a protest on very similar lines

against the conditions at Upper Koncoita, and took the opportunity to

endorse Major Hunt's representations and to protest not only as A.I.F.

Commander, but as the senior representative of the Commonwealth

Government in Thailand.

Lt.-Col. Harris stated later that both protests had a most telling

effect on Col. Banno, who exclaimed upon reading them: "My

God! My God! What can I do?"

The immediate result was the departure of Col. Banno for Burma, and on

his return on 4th June he issued orders that all work was to cease

indefinitely. The rest period lasted only four days.

In the meantime, however, the Camp Commander was to be engaged in more

stormy interviews with the Supervising Officer, who harboured

suspicions that the figures of the sick were being deliberately faked,

but was unwilling to make a direct charge to this effect to Major

Johnston.

After one such scene, Lieut. Fukuda approved the segregation of the

sick in the camp into one area and the establishment of a central camp

hospital for all men classified as "No Duty".

The effect of this was to provide a loophole for the abolishment of

"Light Duty" men, thereby safeguarding "light sick men" from being sent

to work, but this was done only at the expense of throwing additional

work on the already overtaxed medical staff.

157 men were admitted to hospital on this basis, bringing the total,

including staff, to 1000.

It was apparent that a "war" was being waged between the administrative

troops and the Engineers. On 1st June, 300 men were demanded

by the latter, but after an emphatic protest had been made by the

Senior Medical Officer the order was cancelled.

The Engineers retaliated by refusing to supply tools for camp works on

that day and by increasing their demand for 700 men on the following

day, although only 400 men were available. This constant

fight between our officers and the administration continued without

cessation until the completion of the railway.

By 4th June, the Senior Medical Officer reported that the fight against

cholera had been won, but that malaria was beginning to make itself

felt, 40 to 50 new cases being admitted to hospital.

The condition of the men can be gauged from the following figures:-

| Date | Strength | I.J.A. Works | Camp & Hosp Maint. | Sick in Hosp. | Sick in Lines |

| 23 May | 1996 | 1267 | 255 | 124 | 350 |

| 29 May | 1980 | 620 | 312 | 292 | 756 |

| 4 June | 1924 | 319 | 399 | 996 | 210 |

Deaths to the end of May had totalled 56 (1 British) - mainly from

cholera.

Diseases during May were in the following ratios:-

Dysentery 35%;

Cholera 9%;

Malaria 46%;

Tropical Ulcers and Skin 8%;

Beri Beri 1%;

Miscellaneous 1%.

During the next fortnight the position was to deteriorate still

further, the sick figures reaching 1300.

The number of men available for I.J.A. work was further reduced by the

necessity to supply daily 50 of the fittest men and officers to carry

rations from neighbouring camps. A truck had been put in

order to obviate the need of employing men for this purpose, but no

sooner had the necessary repairs been affected than the truck was

transferred elsewhere.

Rations were then drawn from No. 2 Camp and occasionally from others,

and were normally carried in man-packs of loads of 60lb.

On one occasion Lieut. Fukuda ordered that the rations be transported

in ox-carts drawn by the men. With the road in a deplorable

condition, these heavy and awkward carts had to be drawn over a

distance of 26 kilometres to and from No. 5 Camp. It is no

wonder that when the party returned two hours after midnight it was

completely exhausted.

Reversion to man-pack was made after this experiment.

The difficulty in obtaining a steady supply of rations and consequent

reduction in resistance to disease, and the arduousness of the tasks

which the Engineers were calling upon the men to perform was to cause a

further deterioration in health.

The rice ration for fit men was reduced to 500 grams (21 oz.) and that

for the sick men to 200 grams (8 ½ oz.). The

remainder of the day's ration comprised flour 0.08oz; salt 0.66oz;

beans 0.4oz; onions 0.75oz; and meat 2.4oz. Accurate records

were kept of the daily issues, and are available for analysis.

At the same time, relations with Lieut. Fukuda became worse.

On 11th June, in a stormy session, he accused the S.M.O. and Capt.

Howells, who was then in charge of the fit men, of their failure to

co-operate. They had, he said, refused to obey his orders,

and he insinuated that men were feigning disease.

The S.M.O. called upon Fukuda to produce an I.J.A. medical officer to

examine the men independently, but this request was ignored.

Six days later Fukuda discovered that between 30 and 40 officers had

been excluded from the figure of 220 laid down as the maximum number

permitted to remain on camp and hospital duties.

This produced another angry outburst and an order to the effect that

only men on I.J.A. work would be issued with meals in the ensuing 24